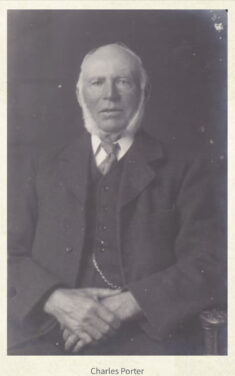

This month we turn our eyes to England and an apple that has become a classic, Porter’s Perfection. The Porter in its name is one Charles Porter (1844 – 1932) of East Lambrook, a small village in the Kingsbury Episcopi parish of the southwestern county of Somerset.

There have been Porters living in Kingsbury Episcopi since at least the mid-16th century, and probably even before that. They were rural folk, laborers mostly. Charles’ father, James, was an innkeeper, owning the Buffalo Inn in East Lambrook from at least 1834. Briefly jailed in 1842 on a smuggling charge, James died of liver failure when Charles was but 15 months old, leaving his widow Jane with four children under the age of 11. She supported her young family as a glover, an important cottage industry in mid-19th century rural Somerset. Money would probably have been tight, so by their mid-teens, both Charles and his older brother William had left school and gotten jobs.

Charles started his working life as a gardener in various parts of Somerset, though never too far from home. By 1881 he was married with two children and had the wherewithal to be farming 20 acres in East Lambrook. In keeping with farms of this time and place, it was probably a mixture of cropland, livestock, and orchards, mostly apples. Like a number of his neighbors, he had a space in one orchard that he used as a nursery, a place to start seedling trees that could be used for rootstock, though one might become a useful apple in its own right. And, like his neighbors, he made cider. That’s who was making most of the cider in England in those days, small farmers with mixed farms, using both equipment and techniques that had for the most part not changed in centuries. However, the scientific rigor of the agricultural revolution was about to hit.

A concerted push for agricultural improvement was one of the defining features of the 19th century. People were developing new breeds of livestock and crop varieties, finding new ways to enhance soil fertility and combat pests and diseases, and pioneering the mechanization and improvement of agricultural equipment. With the exception of the innovative orchard work of Thomas Andrew Knight in Herefordshire, though, research into improving cider lagged until the 1890s. Cider, which had once graced the tables of lords and ladies, was now often seen as a mixed bag, some clean and good but much more deeply flawed. Such rough cider might be acceptable to a farm laborer during harvest, but hadn’t much of a market otherwise.

Robert Neville Granville, a cider enthusiast and engineer living near Glastonbury, got the improvement ball rolling in 1891. In 1893 the trustees of the Bath and West Society, founded in the late 18th century to advance local agriculture, gave Neville Granville the financial support to hire professional chemist Fredrick Lloyd. They also started a cider competition with the stated goal of encouraging the improvement of cider by awarding cash prizes to the best that met certain minimum standards. (Very few prizes were awarded that first year, but in subsequent years Charles Porter’s neighbor Richard W. Scott entered and won often.) Lloyd began analyzing juice samples, making and analyzing single variety ciders, studying yeasts, and evaluating production methods from harvest to packaging. Each year he wrote a detailed report for the annual Journal of the Bath and West Society and Southern Counties Association.

Within a decade this work had caught the attention of the Board of Agriculture, which was always on the look out for ways to build markets and add to farmer revenue. With monies from the Board, as well as from various apple-growing counties in the west of England, a farm suitable for experimentation was identified at Long Ashton near Bristol, and the National Fruit and Cider Institute was launched. This hugely influential body continued to conduct research on cider for the next 80 years, merging with the University of Bristol in 1912 and being renamed the Long Ashton Research Station. Lloyd acted as the institute’s head until 1905, then was succeeded by Bertie T. P. Barker.

It is here that our story (finally) loops back to Porter’s Perfection, for Barker is the one that brought the apple to public notice after learning of it much by accident. He was searching for a supply of Cap of Liberty apples for that year’s experiments when Charles Porter pointed out a seedling tree, growing in one of his orchards, that seemed to be similar. Barker gave it a try, and, he wrote later “the cider made from it proved to be of such excellent quality that each year since that time…the fruit has been procured for trial purposes…the results have on the whole been so good that it is justifiable to regard the variety as one of the best kinds yet tested for the production of a medium brisk [by which he meant acidic], light, bottling cider.” Barker named it Porter’s Perfection as it was Charles Porter “to whom is really due the credit of having …recognized its merit.” The institute had by this time (1912) been producing young Porter’s Perfection trees and was poised to provide them to farmers ready to try this new apple that but for chance might have lived out its life unknown. It remains popular to this day, and the Porter family is still growing it, and others varieties, supplying fruit to Perry’s Cider in nearby Dowlish Wake.

It’s a funny little apple, yellow-green with stripes of red and a thick fleshy stem. Its most remarkable feature, though, is its regular tendency to form fused fruits, usually in twos, but sometimes three or more, hence its other name, Clusters. When walking through an orchard it is hard to imagine mistaking this variety for anything else.

The collection of Porter’s Perfection ciders I tasted through recently–half sparkling, half still–was fascinating, to say the least. None were particularly aromatic, light to medium in their intensity. Not every renowned fermentable fruit is particularly fragrant, of course, Chardonnay grapes being a perfect example. All possessed notable acid, each showing more than medium briskness, to use Barker’s term, and plenty of tannin, though their colors ranged from yellow to gold to amber.

Where they diverged the most was in their aromas/flavors. Most had some fruit character, tending toward the tart parts like skin or peel, the exception being the cider from Haykin Family Cider, which was rather riper and a little floral. Two, from Eve’s and South Hill, were distinctly savory. What was most interesting to me, however, was how several of the older examples were beginning to develop the tertiary flavors we often associate with aged wines, such as cedar and spice. Certainly these ciders have the acid/tannin structure that suggests they’d age well. It would be worth laying in a few bottles to try again in a year, or two years, or perhaps several more.

Here’s the list:

Bauman’s Cider Company, Gervais, OR – lemon, lemon peel, pear skin, gooseberry, twigs, granite, wood; sparkling; 2019; 6.9% ABV

Eastman’s Forgotten Ciders, Wheeler, MI – plum skin, tart apple skin, blood orange peel, gooseberry, cedar, sawdust; sparkling; 2015; 6.3% ABV

Haykin Family Cider, Aurora, CO – lemon juice, blood orange juice, guava, ripe apple, ripe pear, rose petals; sparkling; 2018; 7.7 % ABV (the apples used were grown in Yakima, WA)

Eve’s Cidery, Van Etten, NY – orange peel, pear, gooseberry, brine, soy sauce, clove, cedar; still; 2017; 8.5% ABV

South Hill Cider, Ithaca, NY – apple skin, gooseberry, green plum, grass, brine; still; 2019; 8.4% ABV

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA – grapefruit peel, pear skin, green plum, gooseberry, clove, cedar; still; 2017; 7.4% ABV

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA – tart orange, apple skin, gooseberry, grapefruit peel, clove, twigs; still; 2019; 7.5% ABV