The village grain mill was ever an important feature in the lives of local residents. Not that one couldn’t mill grains at home but, as anyone who’s tried it knows, using a hand mill is laborious and time consuming, and it’s next to impossible to produce anything finer than a course flour. Until the advent of steam power, mills were locate along waterways, the movement of the water serving as the means to turn the giant grinding stones. The mill in the Somerset village of Yarlington was on the River Cam, a bit to the southwest of the village center It was in continuous operation through the 19th century until finally closing in 1906.

As the story goes, the eponymous apple was discovered by Edward Bartlett (1867-1916) growing out of a stone wall near the point where the water left the mill to rejoin the river. Edward’s father, William (1840-1918), purchased the mill some time between 1875 and 1881. William’s mother, Mary (1798-1959, née Humphries), was born in Yarlington, and a member of the Humphries family owned the mill until 1845, which may be why William was interested in it. It could also be that Edward was already working there as a baker boy (he’s listed as a baker in the 1881 census when the family was living at the mill), though he would have been young for the job.

Upon its discovery, the scrappy little tree was dug out and transplanted, possibly in an orchard on the mill property but more likely at the 140 acre farm called Mancroft that William Bartlett owned in nearby Galhampton. By 1891, William and his second wife, Sarah (1841-1917), had moved back to Mancroft, leaving Edward and his brother James to run the mill in Yarlington. There’s no indication that Edward ever was a cider maker, but his father certainly was. Several reports in the local papers note that after various meetings the participants adjourned to Barlett’s farm to enjoy more than a few pints of his cider.

Most apples grown from seed take upwards of 15 to 20 years to bear fruit in any significant quantities. Yarlington Mill must have been an exception, however. By the early 20th century it was producing sufficient quantities of fruit to make enough cider to share with the neighbors. The cider apparently made quite an impression, so much so that several nearby farms had grafted trees in their own orchards which were also bearing fruit. In 1903, the apple was discussed at a cider conference held by the Mid-Somerset Agricultural Society. “Yarlington Mill was another apple very highly spoken of . . . a very vigorous grower,” noted an article published in the 30 October issue of The Shepton Mallet Journal.

About this time it also came to the attention of The National Fruit and Cider Institute, precursor to the more well known Long Ashton Research Station. Researchers there grafted Yarlington Mill into a number of test orchards and began logging annual bloom times and the tree’s growth habits. Apples from the bearing orchards around Galhampton and Yarlington were collected for analysis, and test batches of cider were being made and evaluated. “Not brisk enough for use alone, but of first-rate quality for blending,” one researcher decided. Good quality juice and the preciosity of the tree recommended it to many a farmer, and Yarlington Mill was on its way to becoming a staple in Somerset’s cider orchards.

The apple’s full name is actually Yarlington Mill Jersey, for it is a member of a group of apples sometimes called Jersey types, which includes Chisel Jersey, Coat Jersey, and Harry Masters Jersey, among others. What these apples all have in common is a bittersweet character and conical shape, though neither is unique to apples with the name Jersey. There has been much speculation about that moniker, including that it comes from the word jaisy, which is said to mean bitter in the dialect of Somerset. There has also been speculation that these apples, or at least their ancestors, came from the island of Jersey in the English Channel. There is nothing in the records to substantiate either guess, however.

Jersey, the largest of the Channel Islands, has been an important place for cidermaking since at least the 15th century. Apple varieties were brought in from nearby Normandy, but many local cultivars were developed from seed as well. An important provisioning port, records from the time of Henry the VIII talk of naval ships stopping to take on barrels of cider and complaining about the prices. By the late 17th century, so much land had been turned into cider orchards that the local authorities, concerned about grain supplies, passed a law forbidding the planting of any new ones, although existing orchards could be replanted. Cider was a major export product, and remained so into the 19th century. Both apples and cider are know to have been brought by ship to England’s southern coast, including to Somerset and Devon, and seeds might well have found their way inland.

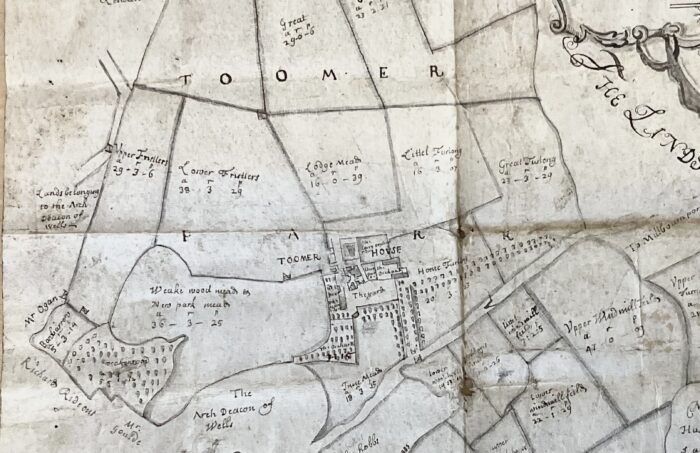

A more interesting, though highly speculative, possibility is that Jersey fruit came to Somerset orchards more deliberately. In the 1760s, a man named Sir Edward de Carteret (1620-1683) bought the manor of Toomer near the village of Henstridge in southeastern Somerset. The de Carterets were one of the oldest and most important families in the Channel Islands with several manors on Jersey surrounded by acres and acres of cider orchards. Ardent royalists, they supported the House of Stuart during the English Civil War, and one member of the family, Sir George Carteret, was rewarded with lands in England’s North American Colonies after the Restoration,which is how the area came to be named New Jersey (also known for its cider).

It takes no stretch of the imagination to think that Sir Edward, and later his son Sir Charles, might have directed that the cider apple varieties they were familiar with be brought to their Toomer estate. Maps from the period show the house surrounded by orchards, just as their estate on Jersey was. Charles didn’t hold the place long, though, as he had both money and political problems, and by 1696 he’d sold it. Several years later he followed the last Stuart king, the unpopular James II, into exile in France. Still, the orchards, and their (possible) Jersey gene pool remained. It is just 10 miles from Toomer to Yarlington, and 18 to Martock, where both Harry Masters Jersey and Chisel Jersey were discovered. It is intriguing to think that Jersey type apples started at Toomer and spread out from there.

Regardless of how Yarlington Mill Jersey got its name, it has been, and continues to be, an important variety for cider in England’s western counties. It has also found its way into American Orchards, though it is no longer part of the U.S. Germplasm Repository in Geneva, New York. After tasting through a group of Yarlington Mill single variety ciders, one has to wonder if somewhere in its travels through the US something got mislabeled, for though most of the ciders had very obvious common features–a rich amber color, pronounced aromatics, and spicy tannins–others were remarkably different both in color and aromatic intensity, not to mention striking different in flavor. Still good, just different.

Ross on Wye Cider and Perry Co., Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, U.K. – dry; roasted apples, clove, cinnamon, tobacco, vanilla, dried orange peel; sparkling; harvested 2014, bottled 2016; 7.4% ABV

Oliver’s Cider and Perry, Ocle Pychard, Herefordshire, U.K. – semi-dry; honeycomb, ripe apple, ripe melon, pear skin, shoyu, clove, butterscotch, leather; petillant; 2021; 5.7% ABV

Stone Circle Cider, Estacada, OR – dry; orange peel, clove, ripe apple, ripe melon, leather, orange peel; sparkling; undated; 6.6% ABV

Two Broads Ciderworks, San Luis Obispo – dry; pear, pear skin, melon, quince, green herbs, lychee, cinnamon, clove; sparkling; undated; 8.5% ABV

Alpenfire Cider, Port Townsend, WA – dry; quince, pear, pear skin, grapefruit, green herbs, just ripe peach; sparkling; 2019; 5% ABV

Bauman’s Cider, Keeved, Gervais, OR – semi-dry; ripe peach, ripe apricot, raspberry, orange, ripe melon, clove, cinnamon; sparkling; undated; 6.8%

Eve’s Cidery, Van Etten, NY – semi-dry; strawberry jam, bread dough, tart orange peel, ripe apple, barnyard, chalk; sparkliing; 2021; 7% ABV