Ask a reasonably knowledgeable cider drinker to make a list of English cider apples, and Stoke Red is unlikely to be on it. This mildly bittersharp apple never became the sort of household name that Kingston Black did, for example, although it has many similarities. It’s one of those apples that forms the backbone of many a cider though seldom seems to be the star. You won’t find old newspaper ads touting Stoke Red, yet dig a little deeper and it becomes clear that Stoke Red has had its fans.

The first part 20th century was a time of great change in the cider world, particularly in the United Kingdom. Up to the late 19th century, cider was almost exclusively a local product. It was made by farmers from their own apples and consumed primarily on the spot. Orchards did double duty, producing fruit on huge trees and carpeted with grass for grazing livestock. The cidermaking could be haphazard for the cider itself just had to satisfy the tastes of the farmer, his family, and his hired help. Only if there was excess would it be sold elsewhere, and even then generally within 50 miles of where it had been made. The Bulmer brothers, Percy and Fred, changed all that.

The Bulmers weren’t the first to start what would become a large scale cidermaking operation. That credit goes to William Gaynor, Jr. when, in 1870, he purchased a hydraulic juice press and began transforming his family’s local Norfolk cider business into one with national ambitions. “It was a defining moment,” writes Ted Bruning in Golden Fire (Authors Online, Ltd., 2012), “the moment when cidermaking stopped being a by-product of farming or estate management and became an industry in its own right.” The Bulmer’s Hereford-based operation got started later, in the 1880s and was soon joined by other cider manufacturers such as Godwin’s, Weston’s, and Showerings. The latter two started out as farmer-based businesses but by the turn of the 20th century were fully focused on large-scale cider production.

Bringing cider into the industrial revolution was, of course, dependent on a reliable and ever-increasing source of apples to provide juice, and that was a problem. By the 1920s, many of the orchards in the west of England, where a significant number of the cider factories were located, were up to 100 years old and had often not received the best of care. They also contained a wild mix of varieties, many unnamed and ill-suited to creating the sort of consistent flavor profiles that average, urban cider consumers had come to expect. This was the view of the scientists at the Long Ashton Research Service (LARS), at least. The bigger problem was that there simply not enough apples being grown for cider. Cider manufacturers had to increasingly rely on using culls of market apples and imports from abroad, particularly France. The latter option worked well enough as long as tariffs remained low, but the general feeling was that it would be better to ensure a robust domestic supply.

In the early days of the National Fruit and Cider Institute, which became Long Ashton upon its jointing the University of Bristol in 1912, research focused on testing apple varieties, provided by local farmers or gathered in the field, through chemical analysis and tasting test batches of cider. As the program and budget, grew LARS expanded its research accordingly. Test orchards were created at or near the research station to investigate the impact of different rootstocks and management practices. Trees of selected varieties were used to start test orchards in Devon, Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Monmouthshire, Dorset, and other spots in Somerset to examine the effect of different climates and soils. Over time, various aspects of cider production were evaluated–wild vs cultured yeast, the use of sulfites, slowing the rate of fermentation by centrifugation, and the impact of storage temperature, among them.

In 1925 in an effort to stimulate more interest in improving and expanding the domestic apple supply, the LARS researchers created a novel cider competition. Farmers wishing to enter were instructed to send in roughly 1,700 pounds of a single variety, which would be fermented into cider at LARS then judged by three prominent members of the British cider community, often principles in one of the large-scale cider businesses. Fermentation by the same people under the same conditions eliminated, as must as is possible, the variable the cider’s character coming principally from cidermaking choices and put the focus right on the fruit itself. The categories were sharps (> 4.5 g/L acid), sweets (< 4.5 g/L acid), and bittersweets (< 4.5 g/L acid plus >2 g/L tannin). (Bittersharp as a category doesn’t appear in the LARS reports until the 1940s.) Kingston Black apples got their own separate category.

This is where Stoke Red comes into the story. Dairy farmer Herbert H. Sealy (1873-1939) entered it into the 1926/27 competition, under the name Stoke Red Stripes, and not only won first prize in the sharp category but thoroughly impressed the staff at LARS. The 1927 Annual Report of the Agricultural and Horticultural Research Station stated “this variety promises to be worthy of a place amongst the best sharp cider apples,” the most celebrated of which was, of course, Kingston Black. Two more entries by Sealy, in 1927/28 and 1928/29, cemented interest among the research staff (“This apple is undoubtably an outstanding sharp variety,” noted the 1928 Annual Report) assuring Stoke Red’s future.

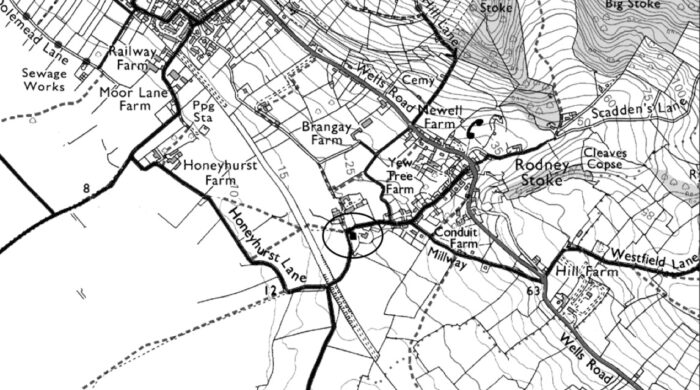

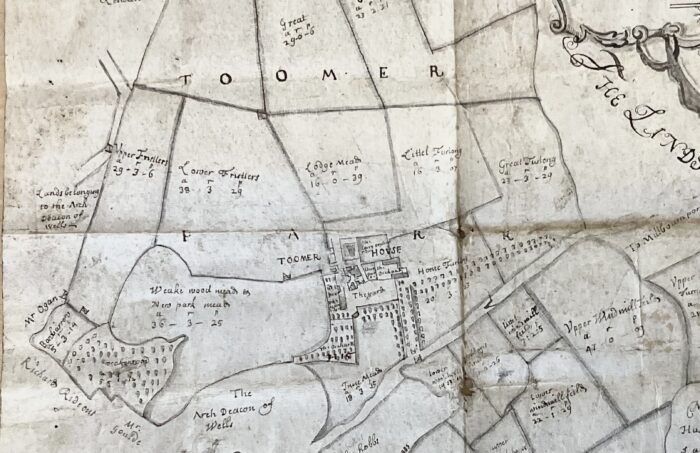

Sealy lived and worked at Honeyhurst Farm just outside of Rodney Stoke three miles from the town of Cheddar, home of the eponymous cheese that has been made there since the 12th century. Honeyhurst Farm was owned by the Tyleys, a family of wealthy yeoman that owned several farms in the area, including Manor Farm and Edgecomb, where Sealy and his wife, Mary Jane (neé Carver, 1871-1951) were living in 1901. One of Sealy’s cousins, his grandfather Edwin’s niece , was the first wife of Honeyhurst’s owner, Charles Tyley (1851-1906), which may be how he came to be a Tyley tenant. It is almost certainly one of the Tyleys that planted the original Stoke Red tree. The apple was well established there by the 1920s as demonstrated by the fact that one of the Tyleys, William James (1882-1943) sent 1700 lbs of Stoke Red to the competition from Manor Farm (next door to Honeyhurst) in 1928.

The staff at LARS was so impressed with the vintage quality of Stoke Red that they almost immediately began including it in their research. They grafted it into the orchard at Long Ashton in 1932 and created trees that were sent for planting intest orchards in Worcestershire, Devonshire, Gloucestershire, and elsewhere in Somerset to see how it would fair under different growing conditions. Follow-up work was a bit hit and miss during WW II, but by the time the LARS cider advisory committee published their short list of recommended varieties in 1947, Stoke Red was on it. It was a slow grower, but was somewhat self-fertile and a reasonable pollinator for other varieties. It was also resistant to a number of troublesome pests–aphids, apple sucker, winter moth, and scab-which led to its inclusion in the LARS breeding program. (It is one of the parents of Ashton Bitter; the other is Dabinett.)

Though Stoke Red’s unruly growth habit and small size, both of which demand extra labor to deal with, have made it a less popular choice for the modern orchard, its other positive characteristics have endeared it to some. One can find single variety Stoke Red ciders on both sides of the Atlantic, though the ones made in the U.K. seem to come primarily from older orchards. Notes of orange and spice seem to be a common flavor through-line, as is the abundant acid and tannin. These ciders did indeed have some similarity to a well-made Kingston Black while at the same time maintaining their own unique character.

Bauman’s Cider, Gervais, OR – dry; passion fruit, orange, lemon, tart apple, plum skin, leather, quince; sparkling; 2021; 7.9%

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA – dry; tart plum. twig, baked apple, clove, orange; sparkling; 2017; 7.5% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA – semi-dry; orange, orange peel, clove, ripe apple, plum skin, twig, baked apple; sparkling; undated; 6.9% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA – dry; lemon, orange, plum skin, yellow apple, clove; sparkling; undated; 6.3% ABV

Burrow Hill Cider, Kingsbury Epsicopi, Somerset, U.K. – dry; plum skin, apple, just ripe pear; sparkling; undated; 8.0% ABV

Wilding Cider Stoke Red #1, Chew Magna, Somerset, U.K. – semi-sweet; orange, ripe apple, wet leaves, twigs, peach, strawberry; sparkling; 2020; 3.8% ABV

Wilding Cider Stoke Red #2, Chew Magna, Somerset, U.K. – semi-sweet; ripe apple, sweet orange, twig, ripe pear, clove, pear skin, rose; sparkling; 2020; 3.7% ABV

Oliver’s Cider and Perry, Ocle Pychard, Herefordshire, U.K. – semi-sweet; sweet orange, orange blossom, ripe apple, clove, cinnamon, nutmeg, ripe plum, dried leaves; still; 2015; 5.5% ABV