This is a tale about a group of apples that is not very familiar to most people–crabapples. First, let’s consider the name. The descriptor crab as used for apples goes back a long way, to the early 1400s at least. In their entry for the Oxford English Dictionary, the good people researching the history of words, whose job it is to know such things, could not decide whether or not it first referred to a cranky, sour person or a wild apple (M. sylvestris in Europe), which were generally perceived to be hard, sour, astringent, bitter, and thoroughly unpleasant to eat. They cite a number of references that could support either choice, then seem to throw up their hands and walk away.

Eventually the word crab apple came to refer to any apple grown from seed, whether planted as nursery stock by a farmer or by chance in a hedgerow, though the latter was looked upon with more suspicion. The association between wildness and crabbiness persisted and was as much philosophical as botanical. Wildness existed outside of civilization, the place where mankind had the opportunity, by the grace of God, to tame its sinful nature. Wildness was antithetical to order and to be discouraged. In the 17th century, apothecary John Parkinson wrote “Wildings and Crabs are withought number or use in our Orchard, being to be had out of the woods, fields and hedges rather than any where else” (Paradisi in Sole. 1629). There was hope for crab apples, though. It was clear that despite their unpleasantness, they could make good cider. “Wee may admire the goodness of God, that hath given such facility to so wild fruits,” noted Parkinson.

A crab’s wild, unpleasant nature could also be transformed. Later in the century, devout Calvinist, cidermaker, and nurseryman Ralph Austen expounded on this point in A Dialogue, or Familiar Discourse, and conference betweene the Husbandman, and Fruit-trees (1672), one of the books he wrote about the spiritual nature of orchards and fruit trees. The Husbandman has a brief conversation with the famous Redstreak cider apple, how it was first called the Skidomore (Scudamore) Crab, but its name changed when people considered its true nature “and now we are everywhere cryed up, and in great esteeme amongst all men.” Later, the other fruit trees explain that the act of grafting itself can convert the “stocks that are of wild kinds, of bitter, harsh, and sower kinds” to the “sweete, and pleasant Nature” of the scion so that they would “bring forth Fruits according to their owne Natures; and the badnesse of the stocks cannot alter the goodness of the Grafts . . .that the God of Nature at first Creation fixed in every individual.”

The connection between crabapples and wildness has never completely disappeared, though modern scientists are more likely to define crab apples by their small size, typically less than two inches across. As it happens, though, many of the apples falling into the small category are descendants of wild Malus species, i.e. something other than our domesticated apples, M. x domestica. (The x here means that domesticated apples are themselves a hybrid of several wild species, mostly M. sieversii, but with genetic contributions from M. sylvestris, M. prunifolia, and M. orientalis.) The connection with tart and/or astringent crabiness has also stayed with crabapples, though each variety has more or less of one or the other.

As a group, crabapples had, and still have, much to recommend them. They have a well deserved reputation for hardiness, which endeared them to people living in less than ideal environments. They have long been planted as pollinators in orchards of domesticated apples, which are often not self-fertile. Their “crabby” nature also made them useful for canning and jelly-making, and for cider. Modern cidermakers are embracing crab apples once again, using them to give a lift of acid to blends, and sometimes fermenting them as single varieties. Here we’ll look as just three of them: Columbia, Kerr, and Manchurian.

Columbia Crab Apple

Columbia is a hybrid between the wild species M. baccata (aka Siberian Crab) and a domestic apple, Broad Green. It was bred by Willam Saunders (1836-1914), founding director of a group of government-sponsored experimental farms established in several Canadian provinces in the 1880s. Son of British emigres of modest means, Saunders has been described as one of the last self-taught natural scientists to rise to prominence in Canada. A pharmacist, entomologist, botanist, and agriculturalist, he developed many hardy plant varieties that could withstand the harsh cold of the Canadian north, including an early maturing wheat.

His apple-breeding efforts started on the experimental farm near Ottawa, Ontario in 1894 with the planting of M. baccata seeds he’d gotten from the Imperial Botanic Gardens in St. Petersburg, Russia. The 1800s was a time of great international horticultural exchange, and using apples that were known to grow well in cold places as breeding stock made sense. In his report on the work, Progress in the Breeding of Hardy Apples for the Canadian Northwest (1911), he noted that M. baccata grew abundantly on the shores of the Baikal Sea, where temperatures typically range from a high of 14˚ C (57˚ F) to a low of -19˚ C (-2˚ F). Columbia’s pollen parent was also Russian, coming to North America in a shipment of scions sent to the Iowa State Agricultural College in 1879 from the Akademi Petrowskoe Rasumowskoe near Moscow. (Its Russian name, наливное зеленой широкой, translates literally as bulk green wide. The fellows at the American Pomological Society seem to have thought that Broad Green was a reasonable approximation.)

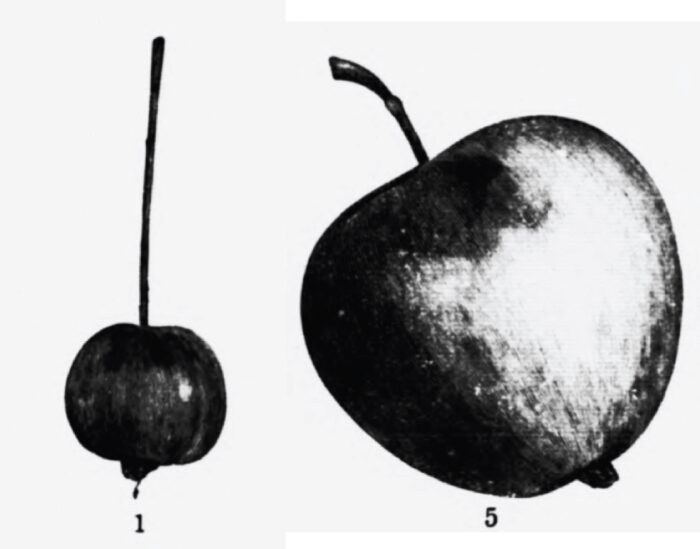

Saunders was not just looking for hardiness, disease resistance, and good flavor but also larger size. At 1.8 inches, (4.5 cm), Columbia was the largest of the crabs in the first group of new ones released to the public and quite a bit larger than at least one of its parents, as can be seen in the images above. Saunders described it as a very strong grower and fair bearer, red, with stripes and dots of a deeper shade, juicy and subacid with a pleasant flavor and slight astringency.

Kerr Crab Apple

Kerr is another Canadian apple, bred at the experimental farm near Morden, Manitoba. Canada’s western prairies are particularly harsh, dry and windy as well as cold. They were also largely treeless until Europeans moved in. Realizing that settlers would be more attracted to a place that wasn’t quite so bleak, the government established several experimental farms in Manitoba and Saskatchewan with the mandate to not only test and develop hardy agricultural plants, but ornamentals and trees and shrubs that could be planted as shelterbelts and windbreaks. The Morden site was located on land purchased from A.P. Stevenson, a “pioneer fruit grower, nurseryman, and the first commercial apple orchardist on the Canadian prairies”, according to William Alderman, author of Development of Horticulture on the Northern Great Plains (1962). Apple breeding started in 1916 with 25,000 seedlings sent from the experimental farm in Ottawa. Of the 21 new varieties released by 1962, 18 derived from this initial planting.

The Kerr crabapple is named for the scientist that made the original cross, William Leslie “Les” Kerr (1902-1986). He wasn’t at Morden long, just a year or two before moving on to become the superintendent of the Sutherland Dominion Forest Nursery Station near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan where he had a long and very productive career. Released commercially in 1952, the crab apple Kerr created has a more complicated pedigree than Columbia. One of its parents was Dolgo crab, imported from Russia in the late 19th century. Dolgo’s parents were believed to be M. x robusta, (a chance hybrid between two wild species, M. baccata (which seems to have gotten around) and M. prunifolia), and a mystery pollen parent. Kerr crossed Dolgo with pollen from an M. x domestica variety called Haralson (parents: Malinda and Wealthy), introduced by the University of Minnesota in 1922 as part of their efforts to breed hardy apples.

You can guess at the Dolgo genes in Kerr Crabs based on their bright candy-red color, though they don’t have Dolgo’s elongated shape . (Dolgo is one word for long in Russian.) It is hearty enough to be grown in Alaska, and, like Dolgo, it can make some very good cider. I’ve only come across one single variety Kerr so far, which seems like a shame. I suspect that it isn’t grow much in the U.S., as Eden sourced their apples from Quebec, something that was a near impossibility during the recent pandemic-related shut downs.

Manchurian Crabapple

Unlike Columbia and Kerr, Manchurian Crab is not a hybrid, but a species of Malus in its own right. Native to Japan, Korea, and other parts of northeast Asia, M. mandshurica, its botanical name, was probably first collected and described in Western literature by Russian horticulturalist Carl Johann Maximowicz (1827-1891). Maximowicz spent five years, starting in 1859, exploring China, Korea, and Japan, studying the unique flora and collecting samples. (There is a dried specimen of M. mandshurica at the New York Botanical Gardens collected by Maximowicz in 1860.) After his trip, he returned to St. Petersburg to work at the Imperial Botanical Gardens, becoming director in 1862.

There is no record of just when Manchurian Crab arrived in North America, but it is easy to imagine that it was in one of the several shipments of seeds and scions sent from St. Petersburg to the Iowa State Agricultural College starting in 1875. Support for this idea can be found the collection records of the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University which show that they received M. mandshurica from Iowa in both 1883 and 1885. It is still grown there today, one of the first crab apples in the arboretum’s collection to bloom in the spring.

Manchurian Crab’s showy, fragrant blossoms are what recommends it to most, though it is also used as a mid-season pollinator in orchards across the U.S. It does not appear to have been used much for breeding, although for the last 100 years or so M. mandshurica was assumed to be a variety of M. baccata rather that a distinct species, so it is rather hard to tell from the records. It’s quite small by apple standards, making harvest a challenge, but the results seem to be be worth it.

All the ciders I tried had the bracing high acidity that you’d expect from crabs (the Columbias were a touch lower), which has allowed for some very elegant aging, especially in the two Kerr Crabs, which six and seven years from harvest still showed plenty of intense primary fruit. Each crab apple could be distinguished from the others–stone fruit in the Kerrs and orange notes in the Manchurians, for example. There were also notable differences in astringency with little to none in the Columbia Crab ciders and moderate amounts in the Manchurians.

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA, Columbia Crab – dry; quince, green apple, pear, nutmeg, oregano, lemon; sparkling; 2016; 7.3% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA, Columbia Crab – semi-dry; green apple, lemon, thyme, bay leaf, nutmeg, pear; sparkling; undated; 6.7% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA, Columbia Crab – semi-dry; green apple, quince, lemon, marjoram; sparkling; undated; 7.4% ABV

Eden Ciders, Newport, VT, King of the North (Kerr Crab) – semi-dry; candied lemon, golden raisin, almond, pear, dried peach, rose, violet, plum, fresh Gravenstein apple; sparkling; 2015; 6.5% ABV

Eden Ciders, Newport, VT, King of the North (Kerr Crab) – semi-dry; lemon, yellow apple, pear, yellow plum, golden raisin, orange; sparkling; 2016; 6.5% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA, Manchurian Crab – semi-dry; yellow apple, lemon, pear skin, plum skin, cardamon, fennel; sparkling; undated; 6.9% ABV

Haykin Family Cider, Aurora, CO, Manchurian Crab – semi-sweet; rose, orange blossom, baked apple, sweet spice, orange rind, lemon; sparkling; 2017; 7% ABV (apples grown in Yakima, WA)

Ploughman Cider, Aspers, PA, Manchurian Crab – semi-dry; lemon, yellow apple, plum skin, orange rind, fennel; sparkling; 2017; 10% ABV

Big Hill Ciderworks, Gardeners, PA, Manchurian Crab – dry; twigs, orange zest, tart plum, lemon, sour orange, cranberry, pear, just ripe nectarine; sparkling; undated; 8.2% (blended with a small amount of Winchester apple)