There are a handful of apple varieties that just say “New York!” to me, and Northern Spy is one of them. Some apples have made homes and reputations for themselves in any number of other places, like Newtown Pippin, but though Northern Spy is grown elsewhere, New York seems to me to suit it best.

Spy, as it is often called, originated as a seedling in Western New York, mostly likely in the late 18th or very early 19thcentury, on land owned by Heman Chapin (1776-1843). The Chapin family had already had a long history in North America by the time Heman was born. The family’s founder, Deacon Samuel Chapin (1598-1675), arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early 1630s, and was one of the early European inhabitants of what became Springfield, MA. He held a variety of important positions in the community and was later memorialized by a rather severe looking statue called The Puritan.

There were, we know, already peoples in the area that had been living there for centuries–the Woronoco, Pocotumtuc, Agawam, and others. Though the European settlers of Springfield ostensibly had a document giving them title to the land, as was the case for many of the other nearby settlements, it is not clear that all the parties involved had the same understanding of just what it meant. In the months before Deacon Chapin’s death this conflicting understanding erupted into real conflict in what is known today as King Philip’s War, which engulfed the region and resulted in the devastation of much of Springfield as well as eleven other local towns. While overt conflict eventually subsided when the colonists caught and executed the Native American leader Metacom (aka King Philip) the deadly fighting certainly took its toll on the survivors on both sides, both physically and psychologically.

One hundred plus years later, after the North American colonies broke away from Britain to become an independent polity, the newly formed United States of America found itself with whole lot of land to the west that up until that point had remained largely unoccupied by Europeans or those of European descent, including western New York. This was land occupied by the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee (aka Iroquois) Confederacy. The Nations had tried to remain neutral during the war, but had eventually picked sides, some fighting with the colonists and others with the British, breaking hundreds of years of precedent and collective government. In the end, sides didn’t matter, though, for all of the Nations lost most of their land, either right after the War or in the decades following it, selling it off to various state governments or land speculators.

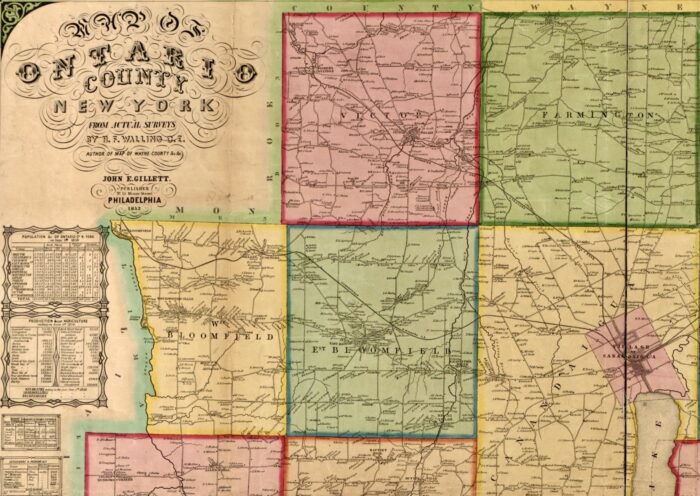

In the late 1780s, land speculators Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham were looking to get in on the land action and asked one of the Chapin war heroes, Gen. Israel Chapin (1740-1795), to help them negotiate their purchase of what is now Ontario County from the Onodowaga (Seneca) It is certainly through this family connection that Heman Chapin and his brother Oliver (1765-1822) found out about the land deal. Each bought a parcel in the early 1790s in what would become East Bloomfield in Ontario County, relocating their families from Salisbury, CT, soon thereafter. This was still wild country, so it would have taken some time to clear land and build houses, their farms slowly taking shape as they created fields for grazing and planted apples seeds to start an orchard.

The first printed mention of the apple Northern Spy was in an October 1842 issue of The Cultivator where it was included on a list of apples recommended for a small garden written by a J.J. Thomas of Macedon, NY. It was not remarked on as being new, suggesting it had come to public notice some time before. That being said, a few years later in publications such as The Genesee Farmer and The Magazine of Horticulture, Northern Spy was described as new and exciting with the promise to become a well-beloved market apple. It’s chief proponents were George Ellwanger and Patrick Barry, the two owners of the Mount Hope Garden and Nurseries, one of the largest of the nurseries that sprang up in early 19th century Rochester, NY. Their motivation was clear for they advertised that they had thousands of 2-year old trees ready for sale, another strong indication the apple had a good reputation, at least locally, well before 1840. There are also any number of ads for barrels of apples selling for up to $2.50/barrel, again suggesting that Northern Spy had been widely grown for some years, at least around Bloomfield and Rochester.

The specifics of where the seeds came from and which of the Chapin’s farms it sprouted on or moved to (some stories add in Heman Chapin’s brothers-in-law Roswell Humphrey and/or Elijah Taylor) are, as with so many apples originating at this time, a little murky. The really interesting question, though, is how did it get a name like Northern Spy? Many of its contemporaries were named for their shape or color (Sheepnose or Golden Russet) or the man (almost always) whose farm it came from (Bullock’s Pippin) or the person who popularized it (Baldwin). But “Northern Spy?” What was that about?

In 1996, a man named Conrad D. Gemmer proposed an answer in the journal for the North American Fruit Explorers journal, Pomona. He claimed to have come across a letter to the editor in an “obscure gardening magazine” dated “around 1853” in which he paraphrases the writer, JBK, as saying that everyone around Rochester, NY, knew that the apple was named for “the “hero” of that notorious dime novel The Northern Spy, but that nobody will come out and admit it.” Gemmer went on to explain that the book had been written anonymously, published “sub-rosa” and circulated among “hard-core abolitionists circa 1830” and the name was probably attached to the apple by “some smart-aleck kid” as both Chapin and Humphrey were “eminently respected gentlemen.” It’s an interesting story, and in fact, there was a novel published in the 19th century called The Northern Spy or, The Fatal Papers written by J. Thomas Warren. The problem, though, is that among the many characters in the book are Confederate soldiers, and since the Confederate States of America wasn’t formed until 1861, it seems unlikely to the source the name of an apple already well known by the 1840s.

That being said, the idea that such an unusual name arose from the literature of the time is an intriguing one. Maybe it came from another dime novel called Double-hand, The Dark Destroyer, or Bashful Bill, The Northern Spy by Lewis W. Carson. The story is set in the mid-1700s in lands occupied by the Onodowaga near the Finger Lakes (and in the general area that was eventually home to many of the Chapins). It features “good Indians” and “bad Indians” (the latter want to kill all the Europeans moving into the area), and brave white men out to avenge the deaths of their family members. It is, in keeping with the dime novel ethos, lurid and slightly ridiculous to the modern reader, but was popular in its day. Though the setting and theme suggest it would have been an attractive read for the early 19th century Chapins, it wasn’t published until 1873.

A better option, at least in terms of the time frame, is James Fennimore Cooper’s book The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground. Published in 1821, it tells the story of a man spying on the British and British sympathizers during the Revolutionary War and was apparently inspired by things Cooper learned from his friend John Jay, delegate to the first and second Continental Congresses, signatory to the Declaration of Independence, and commonly thought of as the “founding father” of U.S. counterintelligence. Jay was also a colleague of both Gen. Israel Chapin and his son Israel Chapin, Jr. Many of the Chapins were soldiers, including Heman and Oliver’s father, Charles. There is even a book about them all, Chapins Who Served in the French and Indian Wars, 1754-59: the Revolutionary War, 1775-83, the War of 1812-15, and others by Charles Wells Chapin (1895). Might one of them have been a spy? No lists from that time exist, so who’s to say.

Suggestive book titles notwithstanding, it may not even have been one of the Chapins that named the apple to begin with. As noted previously, George Ellwanger and Patrick Barry were instrumental in creating a market for Northern Spy, both apples and trees, and as part of that campaign sent a near constant stream of articles and letters to various publications throughout the region. In one piece 1845 written for The Chambersburg (PA) Times, they wrote that the apple was named around 1830 by a man who travelled about offering his grafting services to farmers that might not have the time or skill to do it themselves. This fellow was so impressed with the fruit, the story goes, that he not only named it but took suckers from the base of the tree and sold them to other local farmers, who then grew the fruit for market, which maybe how it came to the notice of Ellwanger and Barry. Northern Spy had not been out of commercial cultivation since, though not grown to the levels it was a hundred years ago.

Usually when I set about to write about an apple I try to find as many examples of cider made from it as I can. This time will be different. The cidermakers at Eve’s Cidery in Van Etten, NY, have been making single variety Northern Spy ciders for many years, and I was fortunate enough to have seven of them (they did not make one in 2018) allowing me to get an idea of how ciders from this apple might age as well as any vintage variation. All had some common elements, such as the high acid that supported graceful aging, as well as lemony aromas and flavors. The oldest, from 2014, seemed a little faded, but that may be due to what seems to have been a rather loose cork (all were closed with a cork and cage). The 2016 vintage was the richest with a fuller body and longer finish. The three vintages starting with 2019 were made using wild yeast and all had a savory quality that wasn’t evident in the others. It was a fascinating experience and one that I am anxious to repeat with other apples.

2014 – dry; green apple skin, lemon pith, cardboard, slightly faded; petillant; 7% ABV

2015 – dry; ripe, dried, and baked yellow apple, lemon peel, lemon pith, yellow plum skin; sparkling; 7.1% ABV

2016 – dry; fresh ripe yellow apple, fresh lemon juice, lemon zest, honeysuckle, baked apple, dried pineapple, almond, yellow pear; sparkling; 9.2%

2017 – dry; ripe yellow apple, lemon juice, slate, ripe peach, rose, persimmon, slight bitterness; sparkling; 7.5% ABV

2019 – dry; ripe yellow apple, lemon drop candy, lemon juice, savory green herbs, brioche, salt, shoyu, tart just ripe peach, yellow plum skin; sparkling; 8% ABV

2020 – dry; ripe yellow apple,quince, ripe peach, lemon juice, pineapple, slate, savory herbs, very fruity; sparkling; 8.4% ABV

2021 – dry; ripe yellow apple, savory green herbs, candied lemon, tart green apple skin, pear skin, just ripe pear, slate, green plum,slight bitterness; sparkling; 8% ABV