McIntosh is such a familiar apple in the U.S. that we tend to forget that its true origins are farther north in Canada. It got its name from John McIntosh (1777-1845), the man that found it growing on land he was clearing outside of Matilda Township in the county of Dundas, Ontario near the St. Lawrence River. He’d arrived there some time in the late 18th or early 19th century from New York’s Mohawk Valley, part of the second wave of European settlers moving into an area long inhabited by the Algonquin, Iroquois, and Wyandot peoples. The first wave had arrived in the 1780s. They were mostly German protestants resettled in England’s American colonies after being ousted from their home in the Palatine by the religious conflicts that were devastating much of Europe. Though historical accounts suggest that they were treated as little more than a cheap source of labor to support the business interests of the controlling English aristocracy, the Palatine ex-pats remained loyal subjects of the crown. Thus were they once again uprooted, heading north into territory still under British rule after the bloody war that turned 13 disparate colonies into the beginnings of the United States.

Known as the McIntosh Red, it seems to have remained a local variety until the 1870s, first noted in a handful of articles in northern Vermont newspapers. “A New Apple” trumpeted the headline over an article written by Guy A. Clough of Braintree, VT to the Vermont Farmer in April 1874. He said that he had accidentally discovered the applewhile traveling in Canada, coming across it in a market and finding it so wonderful that he tracked down its source, John McIntosh’s son Allen. “Your informant became so much interested in . . . this tree, that he traveled over a large section of country . . . in search of rebutting testimony [to its superior qualities], but found none, each affidavit being of the most positive character . . .”, he wrote.

The qualities possessed by McIntosh Red, according to Clough in this and subsequent correspondence, would recommend it to any farmer. The trees bore a decent crop every year, for example, instead of the habit of biannual bearing that many otherwise good apples exhibit, even today. The fruits were large, had an attractive red color, and were reported to keep well into the spring following harvest. But it was the tree’s hardiness and reported resistance to frost damage that seems to have most interested Vermont farmers. Winters in the area could be harsh with temperatures often dropping to -20˚ F, according to one writer. Many of the popular market apples simply couldn’t handle such severe cold. Various horticulturalists had started importing varieties from Russia in hopes of finding or breeding apples that could survive in the coldest climes of Vermont, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, but maybe the native-born McIntosh Red would prove to be a winner for the farmers of the north.

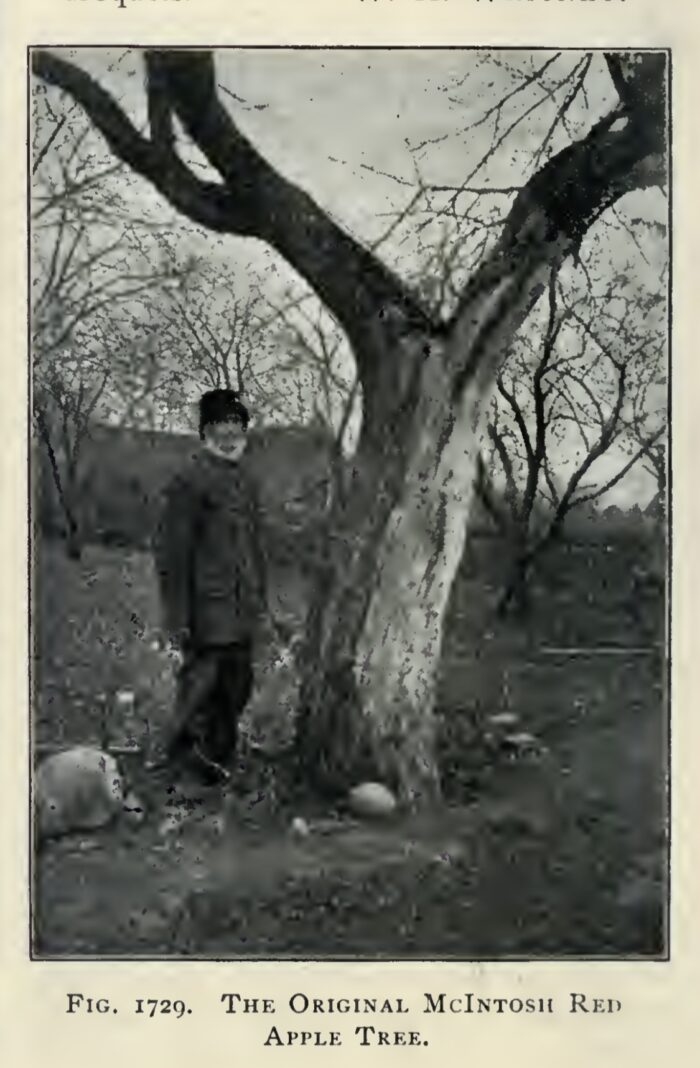

The editor of The Enterprise and Vermonter set out the case in a piece entitled “A Remarkable Apple Discovered” March 1874. “This apple . . . originated in [Matilda, Dundas County] . . . transplanted from the edge of the forest seventy years ago, with perhaps twenty other trees found scattered about in the county, which was then an almost unbroken wilderness,” he wrote. “The other trees have been dead more than thirty years, but . . . the McIntosh Reds . . . are still alive, the tops being thrifty and healthy.” “[I]t is conceded that the frost,” he went on to write, “which is generally so fatal to the apple blossom, never injures this variety in the least. In some instances the ground about the trees has been frozen sufficiently hard to hold a horse, when they were in full bloom, but while other trees were entirely spoiled these were not in the least affected.” This is a singular statement, but if true could make a significant difference to a farmer’s potential bottom line. The papers were soon filled with notices that local nurserymen, including Clough’s son Storr, had grafted McIntosh Red trees ready for sale.

Buying ready grafted trees was something of a new phenomenon. For most of North America’s post-European settler history famers had simply either relied on whatever seedlings were at hand or grafted a seedling tree with a familiar variety themselves. There were a handful of plant nurseries early on, of course, but they mostly catered to the well to do, folks that could afford the significantly higher price tags. The situation had begun to change by the middle of the 19thcentury as selling fruit with recognizable and marketable names increased in importance. The farmer wanting to purchase ready-grafted trees could, then as now, write to a nursery and request a printed catalog, then mail in an pre-paid order and wait for delivery. But there was also another option: the nursery agent. This fellow (it was always a man) would travel the rural highways, knocking on doors with catalog in hand, taking orders for trees and other plants. The order eventually reached the nursery, and some time later the nursery agent would return with the goods. This had tremendous advantages for the rural farmer, for he (also invariably male) would have the opportunity to purchase new and improved varieties that he might not otherwise have know existed, or access stock that was unavailable locally. An article in the February 1871 issue of The Horticulturist stated that “probably nearly three-fourths of the nursery stock sold throughout the United States, is sold by personal solicitation of agents or dealers . . .” a remarkable percentage, if true. The system worked splendidly, too, provided the nursery agent was an honest one (the many help wanted ads stressed the importance of good character).

Unfortunately, this was not always the case. “[A]pparently the great evils the agriculturalist has to deal with are insects and tree-dealers; these two, and the greatest of these is the tree-dealer,” wrote editor James Vick in 1879 (Vick’s Illustrated Monthly Magazine, October). There was, for example, no guarantee that the trees an agent brought to the farm were actually what was ordered, and it took years before the tree would bear enough fruit to tell one way or the other. “I purchased six of those trees [Wealthy] of one of those unreliable beats.,” complained one farmer in a letter to the Vermont Farmer in April 1880. “Three of these trees never leaved (sic) out, and the other three proved to be Soulard crabs.” Anyone could pass themselves off as an agent by ordering a catalog from a well-respected nursery, declare themselves to be that nursery’s representative, then order and pass on possibly quite inferior stock from practically anywhere. The most reputable nurseries took great pains to ensure that their representatives were trustworthy. Some gave their agents special catalogs prominently bearing the agent’s name on the cover or issued official certificates to them, regularly noting these means of authentication in their ads. Others required agents to send in their order books as soon as they were filled so the nursery could monitor sales and makes sure inventory was adequate and properly labeled.

These measures seem to have had an effect, for despite the problems reported in the press, nursery agents proved to be anenormous boon to both the farmer and nursery industry. By the 1890s McIntosh was being grown across the continent, from British Columbia to Pennsylvania. It grows best in cooler climates; in places with warmer autumns it tends to fall from the tree before becoming thoroughly ripe. It is still one of the the top 10 apples grown in the U.S. today and accounted for more that a quarter of the Canadian apple crop in 2018, though there are rumors it is loosing ground to newer, sweeter, and crunchier cultivars.

McIntosh Red was never touted as a great apple for cider, though doubtless more than one found its way into the press as part of a blend. The cidermakers of the 19th century may not have realized what they were missing. A number of 21stcentury cidermakers have taken to McIntosh and are making some throughly tasty ciders with it. The best balance McIntosh’s bright acid with just a hint of sweetness, and when grown well this apple seems to make ciders with real intensity and complexity of flavor, often with an interesting herbal note.

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA – semi-dry; ripe apple, baked apple, sweet lemon, anise, pear skin, cardamon, mango; sparkling; 2017; 8.2% ABV

Gowan’s Heirloom Cider, Philo, CA – semi-dry; ripe apple, baked apple, pear skin, lemon, almond, orange juice, fennel, ripe pear, cinnamon; 2018; sparkling; 6.8% ABV

Bauman’s Cider Company, Gervais, OR – semi-dry; ripe apple,, blossom, cinnamon, ripe pear, lemon juice, pear skin, guava, lemon grass, fresh thyme; sparkling; 2021; 6.0% ABV (apples grown in the Bitteroot Valley, MT)

West County Cider, West-View Orchard “M2”, Sheridan, MA – semi-dry; ripe apple, pear skin, mint, rose, anise, fresh thyme, lemon, yellow plum; sparkling; undated; 6.5% ABV

West County Cider, West-View Orchard “Pura Vida”, Sheridan, MA – semi-sweet; ripe apple, ripe pear, lemon, green apple skin, lemon rind, fresh thyme; sparkling; undated; 5.5% ABV