One of the things that I hoped to accomplish with my exploration of single variety ciders was to get a handle on how terroir – climate, soil, and what have you – plays out with apples and cider, or at least make a start on it. The role that place plays in a cider’s flavor and structure is a largely unexplored idea in the American cider world, and mores the pity. The concept is well established in the wine industry, and if, as fermentation specialist and yeast whisperer Shea Comfort says, cider is wine from trees, then all those environmental factors should be just as important to the flavor of apples as they are to grapes.

When trying to assess the impact of terroir it, is useful to have many examples from both similar and different places. There are only a handful of cider-specific varieties that are that widely grown, although when it comes to cider widely will still probably mean in limited amounts compared to a fresh market apple like Red Delicious, for example. One apple that does fit the bill, though, is the classic Kingston Black.

It would be fair to say that if a cider enthusiast knows the name of only one apple that is, and always has been, grown specifically to make cider it is Kingston Black. It’s an English apple, small, dark red, with some russeting where stem meets fruit. Exactly where and exactly when it was planted and then discovered, and by whom, seems to have been lost to the mists of time. The place can be narrowed down to Somerset, and many writers cite the small village of Kingston St. Mary, about six and a half kilometers north of Taunton, though another possibility is the 18th century Kingston Farm located 22 kilometers to the southwest. The time was probably in the middle of the 18th century, for Kingston Black had developed quite a reputation outside its home area by the 1820s. It was included in the varieties grown by the Horticultural Society of London by 1826, and cider made from it sold by name (Taunton Black, one of its synonyms) in Bristol in 1828.

Pomologist Robert Hogg in his The Apples and Pears as Vintage Fruits (1886) wrote that Kingston Black was first introduced into Herefordshire circa 1820 by George Palmer of Bollitree Castle near Ross-on-Wye. By the end of the 19thcentury it was one of the most widely planted varieties in the shire. Most ciders were, and still are, blends, but Kingston Black was valued as having enough acid, tannin, and sugar to make a good, well-balanced cider all on its own, which may account for some of its popularity. It was one of the apples brought to the U.S. by U.S. Department of Agriculture scientist William Allwood after his late 1890s research tour of the chief cidermaking areas of Europe, though it didn’t really catch on until the 1990s when a new generation of cider enthusiasts began to revive America’s cider industry. Today you can find pockets of Kingston Black in orchards across the country.

The idea that where and how an apple was grown could have a profound impact on the cider made from it first hit me in 2015. I found myself in possession of 15 Kingston Black ciders from around the world and thought it would be fun to invite a group of friends over to try them blind. The variations in both color and flavor came as quite a shock, so much so that we began to wonder if some of the apples involved weren’t actually Kingston Black. Comparative DNA testing of apples from orchards that had yielded two of the most divergent ciders–Farnum Hill Cider in Lebanon, NH and Tilted Shed Ciderworks in Windsor, CA (the apples were grown nearby)–proved that the apples were in fact the same and matched the already established DNA profile of Kingston Black.

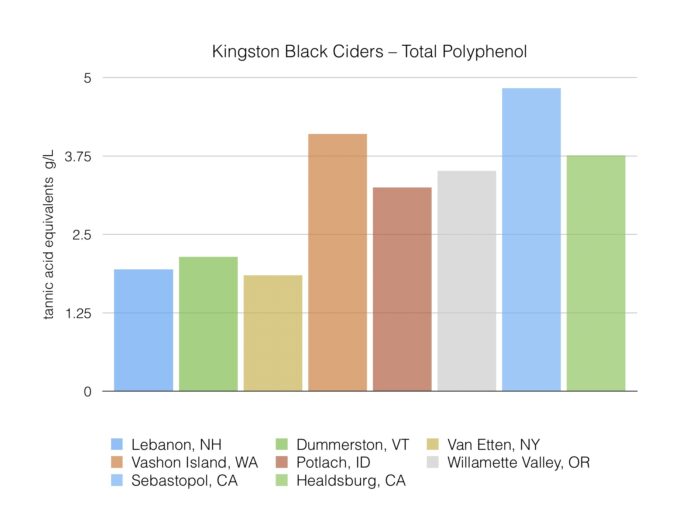

Next came chemical analysis comparing Kingston Black ciders from the northeast with those from the west, averaging samples over several years to take into account the known phenomena of season to season variation in the orchard. To keep it simple, let’s just look at total tannin levels. The amount of tannin in Kingston Black apples grown in England is generally reported to be in the neighborhood of 2 g/L. As you can see in the chart below, the tannin levels in the samples taken from orchards in New Hampshire, Vermont, and the Finger Lakes are pretty similar. The ones from the west coast are considerably higher, sometimes almost double!

There are differences in the glass as well. The ciders I tasted recently, mostly with fan of all things fermented Brandon Buza (@the_fermented_life), were similar yet different. They all exhibited some level of baking spice, clove in particular (consistent with many descriptions of Kingston Black) and all had some sort of citrus component. In the west coast ciders the citrus was orange, sometimes more like fresh juice and at others orange marmalade, and the other flavors were generally riper. In all the other examples, the ciders were tarter and the citrus read more like lemon, either juice or rind, and the other primary fruit flavors zippier. What in the west coast terroirs, for there are many, might account for these differences is open to speculation, although the general aridity leading to water stress in the summer months might be a good guess.

It’ll take more years, more ciders, and more comparative evaluations to come to any more definite conclusion. Wherever you are, you can almost certainly access a handful of Kingston Black varietal ciders, though. Why not get a half dozen, invite some friends over and see what you think?

Tilted Shed Ciderworks, Windsor, CA – dry; orange, clove, cinnamon, nutmeg, ripe pear, ripe yellow apple; sparkling; 2018; 9% ABV

Tilted Shed Ciderworks, Windsor, CA – dry; clove, orange rind, ripe melon, pear drop, ripe pear, VA; sparkling; 2019; 9% ABV

Greenwood Cider Company, Seattle, WA – semi-dry; orange, clove, plum skin, twig, just ripe nectarine, VA; sparkling; 2020; 6.8% ABV

Snowdrift Cider Company, Wenatchee, WA – semi-dry; orange juice, baking spice, nectarine, yellow apple, apple skin; sparkling; 2020(?); 7.5% ABV

Chatter Creek, Seattle, WA – dry; clove, baking spice, ripe apple, lemon, sour orange, plum; sparkling; 2019; 9.5% ABV

Slopeswell Cider, Hood River, OR – dry; sour orange, lemon, lemon rind, nutmeg, nectarine, plum skin, clove; sparkling; 2019; 6.9% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA – dry; orange marmalade, orange juice, lemon, ripe melon, baking spice; sparkling; 2018; 7.9% ABV

Two K Farms, Suttons Bay, MI – dry; lemon, apple skin, clove, pear, pear skin, grape; sparkling; 2019(?); 6.3% ABV

South Hill Cider, Ithaca, NY – dry; rose, clove, lemon, just ripe pear, lightly ripe banana; sparkling; 2017; 7.9% ABV

South Hill Cider, Ithaca, NY – dry; lemon juice, clove, green apple, green plum, salt, just ripe pear; sparkling; 2019; 7.9% ABV

Eve’s Cidery, Van Etten, NY – dry; lemon, baking spice, lemon pith, plum juice, pear; sparkling; 2017; 8.5%