There was a time in the 19th century when the Harrison apple was one of the most famous cider apples in America, but its history reaches back much further.

It takes it’s name from Samuel Harrison (1684-1776). Samuel’s grandfather and great-grandfather, both named Richard, came to North American with their families from West Kirby, a small town on the Mersey River in Cheshire, England. Part of the Great Migration of religious separatists, they arrived some time around 1640 and by 1644 were among the first residents of the town of Branford on the north side of the Long Island Sound. This area had been the land of the Quinnipiac people, but disease and war with both English and indigenous neighbors had taken it’s toll, and it was now part of the New Haven Colony, founded in 1638.

Moving to a new continent did not actually mean that people were free from government control of their religious lives. The governing principles in each colony, especially in the north, were closely tied to the church. The right to land was often tied to church membership, for example, and different churches, or groups of churches, had varying ideas about what it took to become a member. The New Haven Colony’s ideas were considerably stricter than the neighboring colony of Connecticut, so the decision to merge the two in the mid-1660s set off a major rift among New Haven’s residents.

Thus it was in 1666 that Richard, Jr. and family (Richard, Sr. died in 1658) followed the Branford congregation of Reverend Abraham Pierce to the newly English land of New Jersey where they founded the city of Newark on land purchased from the Lenni-Lenape. Richard was granted one of the first town lots, expanding his land holdings in 1675 to include an area known as the Mountain (now West Orange, NJ), which was where the tree that became the first Harrison apple was planted.

The planter was Samuel Harrison, Richard’s grandson. Samuel was an enterprising sort, owning not only extensive lands but the area’s only sawmill, a fulling mill, a blacksmith and carpenter’s shop, a boat that ferried people and goods between Newark and New York City, and, later in life, a cider mill. According to his son, another Samuel, he got a large number of seedling trees from a Mr. Osborne, a descendant of one of the first families in the New Haven Colony but now in South Orange, some time around 1713. (Personal connections were as important then as they are now.)

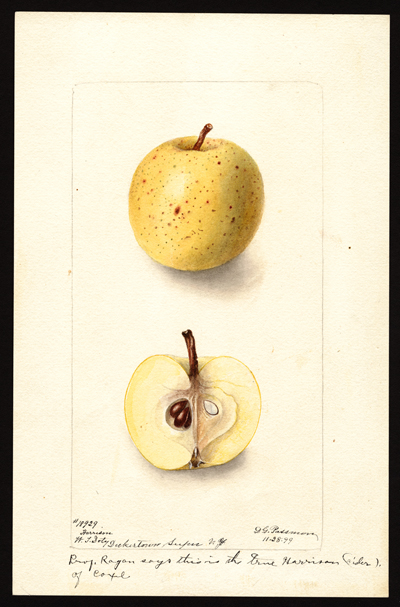

By the luck of the draw, one of these seedlings turned out to be a superior apple for cider. Exactly when this was recognized is so far lost to history. The first written account appears in the American version of Anthony Willich’s Domestic Encyclopedia, edited and augmented with information about American apples in 1804 by Dr. James Mease. Called also the Long Stem and Osborne apple, Mease describes the fruit as “of a moderate size, and of a rich dry taste, with a tartness that renders its sweetness agreeable and lively . . . keeps well a long time, and answers well for culinary purposes.” This is not a particularly detailed description, and nurseryman/orchardist William Coxe did better in A View of Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider (1817). “The shape is rather long,” he wrote, “and pointed towards the crown–the stalk is long. . . the ends are deeply hollowed; the skin is yellow, with many small but distinct black spots, which give a roughness to the touch . . .” Both authors describe the cider as “clear, high colored, rich, and lively” and “and of great strength commanding a high price in New-York, frequently ten dollars and upwards per barrel. . . .” Mease goes on to say that no less a figure than General George Washington preferred it to cider made from another famous cider apple, the Hewes’ (aka Hughes’) Virginia Crab. High praise indeed from a Virginian, if true.

The spread of the Harrison’s reputation can be traced through the young nation’s newspapers. Ads for Newark Cider made from Harrison apples (or simply Harrison Cider) appear in the New York Post starting in 1808, followed by Pennsylvania, south into Maryland, the Carolinas, Arkansas, Georgia, and Kentucky, north and west into Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, Kansas, Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, and eventually all the way to California by the 1880s. Harrison Cider was shipped to the West Indies by the 1840s. Nurseries advertised grafted trees for sale in New York as early as 1804, and in Missouri, Nebraska, Kentucky, and North Carolina in the 1850s and 1860s.

Demographics within the United States were changing, however. The waves of immigrants swelling the U.S. population were largely from countries where cider was not an important drink, and competition from beer and whiskey increased significantly. Newark and its environs were shifting from orchards to industry, as were many other parts of the east coast. Furthermore, at the turn of the 19th century more and more states were enacting laws prohibiting the production and consumption of alcohol. These and other factors encouraged farmers to shift from growing apples for cider production to fruit for the fresh and processing markets. This shift wasn’t absolute, of course, and Harrison cider could still be found in any number of places. It was, for example, the beverage of choice for the annual sheep-roast dinner held by the Crocodile Club, a group of socializing Connecticut politicians, at the Lake Compounce resort owned by the Norton family near Hartford. In 1907 the local papers reported that Norton’s Cider Mill had made 80,000 gallons of Harrison cider that season, some of which would be enjoyed by the Crocodiles.

Contrary to popular narrative, Harrison didn’t completely disappear post-Prohibition; Neenah Nursery in Wisconsin was advertising trees for sale in 1952, for example. Apple markets and consumer tastes had changed, however, sending farmers in a different direction. The intent to reverse that course, at least for Harrison, may have been what sent Vermont orchardist Paul Gidez to Essex County, NJ in 1976 in search of old trees. Good fortune helped him find a few, and he tried to establish an orchard of Harrisons in New England, with limited success. He also gave scions to Virginian Tom Burford, apple enthusiast/explorer, who became the Harrison’s champion. It took a few years, but Harrisons are once again being grown across the U.S. as the interest in cider and old apples has grown.

Where there are apples there will soon be cider, of course, and it is now possible to find a range of Harrison single varietal ciders on the market. I recently conducted a blind tasting of six of them, all from harvests done in 2018 or 2019 and grown in different parts of the country, notably Virginia and Washington. I am happy to say that the 19th century writers were dead on. These ciders all have the richness of flavor that they describe, some with more acid, some with a little less, and are medium to full-bodied. What is interesting, though, is that each had a common aroma/flavor, that of sweet, ripe orange, sometimes veering in the direction of mandarin.

Think about pairing these ciders with a dish that has some richness, like seafood or chicken with a butter or cream-based sauce or a creamy white cheese. An umami-rich soup would be a fine choice, too.

Here’s the lineup with some brief notes:

Albemarle Ciderworks, North Garden, VA – orange, orange blossom, fresh ripe apple, apricots, peaches, and mango; 9% ABV

Potter’s Craft Cider, Charlottesville, VA – orange zest, ripe apple, pineapple, peach, and mango; 8.2% ABV

Wise Bird Cider Co., Lexington, KY – orange, pear skin, slightly under-ripe nectarine, and tart plum; 8.1% ABV

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA – baked apple, baked pear, orange peel, clove, and nutmeg; 8.3% ABV

Tieton Cider Works, Yakima, WA – mandarin orange, pear, and asparagus; 6.9% ABV

Haykin Family Cider, Aurora, CO – baked pear, orange zest, and guava; 7.9% ABV (the Harrisons used by the Haykins were grown in Yakima, WA)