The golden days of August are a time of great abundance in California’s Sonoma County. Farmers markets and home gardens alike are bursting with ripe tomatoes, squash, and peppers. The late summer air around the small town of Sebastopol is perfumed with one of the county’s historic bounties, Gravenstein apples, their harvest celebrated there for more than 100 years. It’s an old apple, and as is the case with most old apples, its origins are a little muddled. Did it come from Italy, Denmark, or Germany and how did it find itself on the other side of the globe in California?

A very early, and perhaps the first written description of the Gravenstein apple was made by Christian C. L. Hirschfeld (1742-1794), a hugely influential writer on gardens and garden design. In volume 1 of his Handbuch der Fruchtbaumzucht (1788) Hirschfeld writes that though the apple originated in Italy it took its name from an estate held by the Dukes of Augustenburg, a lesser branch of the House of Oldenburg. (Other branches sprouted such notables as the late Prince Philip and Catherine the Great.) It was a summer residence in Gråsten (Gravenstein in German) near Sønderborg, which is now firmly in Denmark. During the 18th, though, this part of Jutland was not in Denmark proper, but was a separate duchy in the Holy Roman Empire, which may account for some of the confusion as to whether the apple arose in Denmark or Germany.

Hirschfeld knew the grounds around the castle for he wrote a very detailed description of them in 1782. He does not mention seeing any orchards, though there were pockets of fruit trees here and there. That same year, though, Hirschfeld also wrote about a nursery business on the island of Als, likewise near Sønderborg, owned and run by the Vothmanns. It is from the 1802 writings of Nicolai Vothmann, grandson of the nursery’s founder, that we get a few more details. From 1689, Peter Vothmann (1666-1731) was a gardener at a ducal estate on Als owned by the von Schleswig-Holstein-Sønderborg-Augustenburg family. Vothmann leased a plot of his employer’s land in 1695 to start a nursery, the first in the area. Beginning with kitchen vegetables, he soon was grafting and selling fruit trees, borrowing money to buy the land in the late 1720s. The loan was still outstanding when he died in 1731 leaving his second wife Maria, née Thun (1678-1765), struggling keep the business afloat.

As it happens, Peter Vothmann’s son Hans Peter (1712-1797) had just begun a horticultural apprenticeship at the Gravenstein estate. According to Nicolai, Hans Peter’s son, there was a single tree in the gardens “which had been brought there from Italy several years ago…called Ville Blanc1,” which was known for it’s excellent flavor. The fact that it bore enough fruit to have developed a reputation suggests that it had been there a while, but how it got there and when Nicolai does not say. Wanting to help his mother, Hans Peter took as many scions from this tree as he could, grafting them to seedling rootstock in the family nursery and selling the results. Eventually he returned to Als and took over the nursery. According to Nicolai, who joined the business after the death of his brother Johann Georg (1755-1788), Hans Peter originally kept the name Ville Blanc, but eventually started calling the apple Gravensteiner so that it would not be confused with another apple, Caville Blanc, which he thought was similar, though not as good.

It is curious that this supposedly Italian apple, whether it arrived in Sønderborg as a single grafted tree, scion, or seed, had a French name. Perhaps this is why some writers over the years have suggested it originated in Savoy in the western Alps. This historic region is now divided by the French-Italian border and, as is common with border areas, changed hands many times due to its strategic value. One of its common historic languages was French.

The Vothmann nursery shipped trees throughout Northern Europe, as far away as Norway and St. Petersburg, according to Hirschfeld. It was being grown in Scotland and England by the early 1820s, and New York state by 1829, imported by a German nurseryman named C. Knudson, beginning its journey to the western frontier. At this point in American history the “western frontier” meant the states of Indiana and Iowa, what we now think of as the middle. That frontier line was rapidly evolving, however, as Anglo-European settlement pushed inexorably toward North America’s Pacific coast, taking its fruit culture with it.

There are two competing stories about Gravestein’s eventual arrival in northern California. The first involves a group of Russians who, in 1812, established a fur trapping and provisioning settlement called Fort Ross on the coast of what would become Sonoma County. The existing records show that apples were first planted there in 1820 obtained from a shipment of trees brought in from the nearby Spanish town of Monterey. It is hard to imagine that these were anything but seedling trees and there is nothing in the documentary record to suggest otherwise. There seem to have been a couple of old Gravenstein trees growing in the remnants of the Russian’s orchard by the 1920s, but the property had changed hands several times in the ensuing years and those owners also planted orchards. Named, and therefore grafted, varieties don’t appear in the record until the 1870s.

A much more likely scenario is that the apple came west with the nurseryman Henderson Lewelling, or Luellling as he spelled it once he got to the west coast (1809-1878). A fascinating character, Luelling was born in Randolph County, North Carolina. It was a rugged and rocky place where the soils were largely played out by the time his family moved to the newly opened up territory of Indiana in 1822. He started his first nursery there. A devout Quaker and abolitionist, Luelling moved on to the new town of Salem, Iowa in 1837, along with this brother John and their growing families, both to start an expanded nursery business and participate in the Underground Railroad, sheltering enslaved people escaping from the nearby slave-state, Missouri. Gravenstein was probably one of the apples they grafted and sold for Luelling made regular trips to east coast nurseries, particularly the one owned by the Prince family on Long Island, New York, where he could access scionwood for the latest most popular fruit varieties. The Prince nursery started listing Gravenstein for sale some time between 1833 and 1837.

Apparently long fascinated with seeing the farthest western part of the continent, in 1847 Luelling made the decision to uproot his family once again and head for the Oregon Territories. The story of his journey as told by David Diamond in Migrations: Henderson Luelling and the Cultivated Apple, 1822-1854 (2004) makes for compelling reading, particularly if one has spent any time hiking in the still fiercely wild and beautiful areas they traversed. They built a wagon outfitted with soil-filled boxes just to transport the some 700 plants they took with them–apples, pears, cherries, and grapes, popular varieties that Luelling knew would sell–pulled by a team of six oxen. Setting out in April, 1847 it took them a full eight months to make the trip of some 2,600 miles from Salem to the Oregon Trail’s end near modern day Portland. Many families from the area went with them; one third died en route. They forded numerous rivers and creeks, crossed grassy prairie lands and arid alkali pans. They climbed and descended steep ridges, extra oxen pulling on the uphills and the team hitched to the backs of the wagons on the downhills to prevent them from careening away and crashing at the bottom. Half of the plants died from killing frosts as they crossed the Rocky Mountains in mid-July. Luelling’s wife, Elizabeth, spent the entire journey pregnant, giving birth to their ninth child about two weeks after their arrival in Oregon.

Once arriving at their destination it took several more months before Luelling found and bought property he thought suitable, rejecting the easy grasslands of the Willamette Valley for a forested site on the east bank of the Willamette River near Johnson Creek. There was an existing cabin, but not much cleared land for an orchard–it took two months to clear one acre of the old growth trees and finally get his young fruit trees into solid ground. Gravenstein, Yellow Newtown Pippin, and Esopus Spitzenburg were among them, according to a list provided by Luelling’s son Alfred, for most of the apples had survived the journey. They had spent an entire season, from flowering to dormancy, in that rolling wagon, now finding a completely new home in Oregon’s rich soil. There was a mad scramble to find or plant seedlings that could be used as rootstocks, but several years later Luelling or his partner, William Meek, were making periodic trips through Oregon and southern Washington with a nursery wagon filled with trees ready for planting.

Luelling probably already had his eye on the California market from the beginning, though there still weren’t that many settlers living there. That changed pretty quickly when gold was discovered in 1849, setting off a stampede of prospectors, miners, and the myriad of other newcomers that set up businesses to support them. John and Seth Luelling, who had by now joined his brothers in the Oregon enterprise, even tried their hand at panning for gold, though they didn’t find much. They did, however, start another nursery orchard in 1850/51 on land in the mountainous gold fields west of Sacramento owned by Enos Mendenhall, another one of the Salem Quakers that had traveled west with the Luelllings. This nursery orchard was, no doubt, the source of the grafted trees sold by Sacramento auctioneer J.B. Stark in March of 1854, the first mention of Gravenstein’s existence in California. Captain Joseph Aram of San Jose, who had arrived in California in 1846 and some years later started the first nursery in Santa Clara County, exhibited Gravensteins at the state fair of 1856. J.W. Osborn showed Gravensteins from his Napa Valley orchard at the state fair of 1858. An early mention of Gravensteins in Sonoma County came in January 1862 when the J.L. Mock nursery included it in an ad with trees for sale in the Petaluma Argus. And so plantings of Gravenstein spread until by the early 20th century is was one of the most widely planted varieties in Sonoma County.

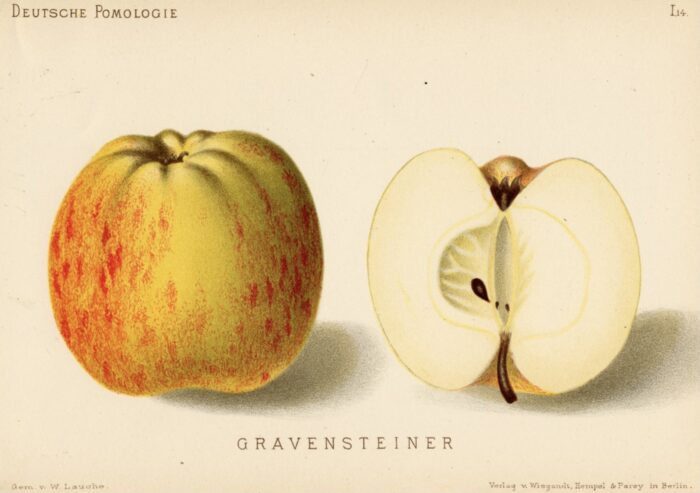

Gravenstein seems to have always had a host of devoted fans. “The Gravensteiner is unequivocally the king among the apples,” wrote Hirschfeld, “[i]t is also everywhere . . . [t]he shape is Caville-like, yellow in color, bright red on the sunny side, sprinkled with red stains [stripes] . . .The smell is sublime and melon-like; the flesh is very white, firm, rich, and has a lovely taste . . .The tree of this glorious apple grows very quickly and bears plentifully.” Other pomologists were likewise enthusiastic. “This apple is equally useful for the table and other purposes,” wrote William Kendrick in 1833. ‘[I]t not only affords excellent cider, but also when dry a very palatable dish” (The New American Orchardist).

Though it has chiefly been used as a processing apple in the U.S.–dried, in sauce, for pies–a number of west coast cidermakers have recently embraced Gravenstein’s cidermaking potential. One might expect Gravenstein ciders to be all low tannin, but several in this group had pleasant levels of astringency and fuller body (Dragon’s Head, Tilted Shed, Humboldt Cider). Their most common feature was flavors of various tart citrus fruits, sometimes zest and other times juice. Several of the examples I tried had been in the cellar a while and had suffered for it (they are not included here), suggesting that Gravenstein ciders may be best consumed while fairly young and still showing their bright, zesty fruit character.

Bauman’s Cider Company, Gervais, OR – dry; apple skin, pear skin, lime juice, lemon rind, green apple, barely ripe peach, honeydew melon; sparkling; 2020; 6% ABV

Dragon’s Head Cider, Vashon Island, WA – dry; quince, tart orange juice, lime juice, coriander, barely ripe nectarine, green herbs; sparkling; 2018; 6.9% ABV

Hidden Star Orchards, Camino, CA – semi-dry; butterscotch, lime zest, nectarine, plum skin, mandarin orange; sparkling; 2017(?); 6.9% ABV

Tilted Shed Ciderworks, Windsor, CA, Inclinado Espumante – dry; grapefruit zest, dried herbs, tart apple, candied citrus peel, lightly floral, VA; sparkling; 2020; 8% ABV

Wildcraft Ciderworks, Eugene, OR – dry; dried twigs, straw, lime juice, apple skin, VA; sparkling; 2020; 6.8% ABV

Humboldt Cider Company, Eureka, CA – semi-dry; cooked apple, lemon zest, nectarine, quince, hay; sparkling; 2020; 7% ABV

Gopher Glen, San Luis Obispo, CA – dry; plum skin, lime, gooseberry, coriander, slight VA; sparkling; 2018; 8% ABV

- Vothmann, N., Some Remarks About Fruit Culture on Als, Schleswig-Holsteinische Vaterlandskunde, 1802, pages 1 – 28