So many of the apple varieties that come up in conversation when talking about cider have long histories, occasionally well documented but more often not. GoldRush is different. It is a thoroughly modern fruit, the product of focused 20thcentury science.

Up until fairly recently in the history of the apple new varieties arose solely by chance, created at random by busy insects and scattered by hungry bears. Although humans have for millenia been singling out and perpetuating plants with traits that they liked, the idea that one could selectively breed new cultivars didn’t arise until the 18th century in the wake of the Scientific Revolution. The first breeder of apples, or at least the first to write about it, was British horticulturist and pomologist Thomas A. Knight (1759-1838). He had been experimenting with cross breeding peas and other plants, and, believing that the cider apples then in use were coming to the end of their natural life span, he decided to try to develop new apples as well. Some, like Downton Pippin, are still available today.

By the late 19th century, professional scientists at universities and state-sponsored agricultural stations had gotten in the apple breeding game. Breeders in Minnesota were working on varieties that could withstand the bitter winters there; the New York Agricultural Experiment Station was working to improve the already popular Mcintosh. Soon scientists were looking to develop cultivars that would not fall prey to a variety of pests that negatively impact apple growers. As science came to a better understanding of the mechanism of inheritance, that knowledge was enthusiastically applied to the creation of new and improved apples. GoldRush is product of these efforts, coming out of a program seeking to create cultivars resistant to apple scab.

Apple scab is caused by a fungus, one that originated in Central Asia and that since the 19th century has spread throughout the apple-growing world. It infects pears and other related plants, too. It blights both the fruit and the leaves; the latter die and fall off while the former become blemished, unsightly, and unsaleable. Cosmetics might not be such a big deal for fruit that is intended for the cider mill, but if the leaf drop is severe enough over successive years scab can end up killing the tree. There are sprays, of course, but fungicides have their own potential issues, including residues on the fruit and in the environment, plus the added costs of the spray and labor to apply it.

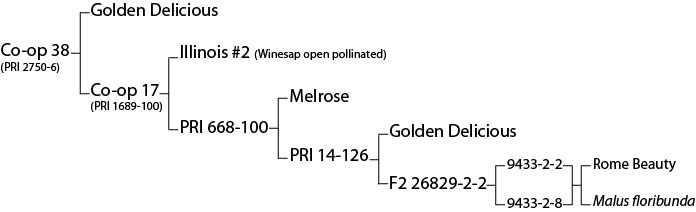

It is with these things in mind that a group of scientists got together to breed new scab-resistant apples. It started in 1945 as a collaboration between J. Ralph Shay at Purdue University and L. Fredric Hough at the University of Illinois. In the early 1940s, Dr. Hough had discovered what appeared to be a single gene in a Japanese crabapple species, Malus floribunda, that made the progeny that carried it resistant to scab. This discovery became the basis for the collaboration and the larger program that grew out of it. Other scientists at the University of Illinois stayed involved when Dr. Hough subsequently moved to Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and since then, the crosses developed by the program are known by the acronym PRI.

The seed that became GoldRush was first planted in May 1973 at Purdue’s research farm in West Lafayette. It came from a cross made in Illinois–Golden Delicious and Co-op 17, a great-great-grandchild of one of the original M. floribunda cultivars (new varieties deemed worthy of additional study were given the identifier Co-op plus a number. GoldRush was Co-op 38 until it was deemed worthy of commercialization). It took seven years to determine that the seedling was interesting enough to pursue further and released for advanced testing. By the time it was finally introduced to commercial nurseries in 1994, GoldRush, as it was now known, had been evaluated at Purdue and Rutgers, and by private growers in California, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Washington, as well as Bologna, Italy.

Twenty-one years from seed to release seems like quite a long time, but in the typical life of an apple tree planted at random that’s practically lightening speed. Consider that a tree started from seed can take as many as seven to ten years to fruit for the first time. Then someone needs to discover it and wait possibly another ten years to see if it produces a decent crop and has something else to recommend it, good flavor and/or texture. GoldRush had the benefit of having a group of people watching it from day one, knowing just what they were looking for. Once it passed its first test, resistance to scab and other major diseases, it could be sped into wider trials to determine its over all value. Add in the time from the first generation of M. floribunda crosses, and the apple was nearly 50 years in the making.

GoldRush, named for its golden color and “rush” of flavor, had, and has, a lot going it. It bears fruit every year if not overcropped, and it’s a good size, an important consideration for an apple destined for the fresh market. It has a firm, crisp texture and what has been described as a spicy, rich, full flavor and sprightly acid. It can keep well in storage for as long as seven months without losing either, another important feature. The acid and the rich flavor are two of the things cidermakers mention in particular when you ask what they like about GoldRush. For though its intended destiny was the local supermarket, GoldRush has found a home in many a cider program as well, especially on the East coast where it is the most widely grown.

That acid and rich flavor were on full display in the ciders I tried recently all of which exhibited a range of tropical fruit notes in amongst the flavors of citrus and flowers. A few had been aged in oak, and while the notes of vanilla were a nice touch, the oakiness did seem play down the primary fruit flavors a bit. Two ciders in the group were at least five years old and still going strong, all that acid helping them to age quite gracefully. For those of you thinking you want to avoid a cider with any residual sugar, keep in mind that a little can be just what an acidic cider needs to achieve the right balance.

Wise Bird Cider, Lexington, KY – semi-dry; pine, pineapple, lime, lemon, green herbs, honeysuckle, passionfruit; sparkling; sparkling; 2019; 6.7% ABV

Albemarle Ciderworks, North Garden, VA – dry; lime, grapefruit, lemon, pineapple, green apple, pear, ripe peach, nutmeg, pine; sparkling; 2017; 9.9% ABV

Ploughman Farm Cider, Aspers, PA – dry; vanilla, pine, pineapple, lemon, lime, cedar, green apple, sweet orange; sparkling; 2019; 7.3% ABV

Westwind Orchard, Accord, NY – semi-dry; vanilla, pineapple, rose, lemon, slightly feral, VA; sparkling; 2016; 7.4% ABV

Manoff Market Gardens & Cidery, New Hope, PA – dry; vanilla, coconut, lemon, lime, wood, apple skin, pineapple pith; sparkling; 2019; 8.5% ABV

ANXO Cider, Imperial Blanc, Washington, DC – dry, lemon, lime, pineapple, lychee, melon, VA; sparkling; 2020; 8.3% ABV