The global trade in fresh fruit amounts to about 80 tons a year with a value of roughly 75 billion dollars. Bananas, limes, grapes, mangos, pineapples, oranges, pears, blueberries, strawberries, and kiwis zip around the world by air, sea, train, and truck. Most of us don’t give the fact that our fruit has traveled so far a second thought. The mass globalization of the fruit trade is relatively modern phenomena, however, and there’s an argument to be made that it was pioneered by an apple, and an American apple at that, the remarkable Newtown Pippin.

Newtown Pippin was born on Long Island in the village of Newtown (now Elmhurst in Queens County) on land owned by one of the Moores, Gershom or Samuel (historical accounts differ). Their father, Rev. John Moore, had been one of the village’s founders in the 1640s, and the original tree was probably planted not long after. At the time, New York was still New Netherland under the control of the tolerant Dutch. That lasted until 1664 when the Dutch governor turned over all the territory that they “owned” in the area to the British and their four threatening war ships, despite the fact that the two countries were technically at peace. The good folk of Newtown had declared their allegiance to England’s king, Charles II, some months before, so local life didn’t change much. In the long run, though, it made it easier for the villagers to significantly expand their geographic horizons.

The apple’s next move was probably to what would become northern New Jersey. Long Island’s land was finite and already largely spoken for. Since farms had to be a minimum size to support even one family, younger sons were forced to move elsewhere if they wanted farms and families of their own. Farming in this age was largely about subsistence, growing enough food to support oneself and one’s family, though having excess to sell or trade was an important part of the economy, too. Access to a waterway was key, roads being few and far between (and bad to boot). Thus did many of the sons of Newtown, including several of the Moores, begin the 18th century by moving to land between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Most settled in Hopewell along the east side of the Delaware, giving them market access to the largest city in North America at the time, Philadelphia. The Moores that moved to Hopewell probably brought Newtown Pippin with them, though nothing has been found in the documentary record to confirm this (so far).

What the Moore family had undoubtedly figured out was that not only was Newtown Pippin a tasty apple, it was a perfect apple for shipping, firm enough that, if packed well, it didn’t bruise. It kept well for months, even without refrigeration, and even got more complex and aromatic with time. (Anyone who has inadvertently kept a case of Newtown Pippins in the back of their car for a week and been enveloped by the rich, tropical aromas they emit can attest to this.) Others would have noticed this, too, and gotten scion wood to graft trees of their own. By the mid-18th century, advertisements for land with bearing orchards of Newtown Pippins were appearing in various colonial newspapers–the New York Gazette (1751), Pennsylvania Gazette (1752), and Virginia Gazette (1766), for example. Nurserymen were advertising grafted trees for sale as early as the 1750s, significant in an era when planting a new orchard from seed was commonplace. Farmers were selling apples in nearby towns, and shipping them to the plantations in the Caribbean where land was more profitably used for sugar production, not food.

Then, in 1758, Benjamin Franklin, settled in London as a newly appointed colonial agent, wrote home to his wife Deborah chiding her for not having sent him any apples. “Newton Pippin would have been most acceptable,” he wrote. Good wife that she was, she soon did, making them the first American apples to cross the Atlantic. Franklin was happy to share them with his friends, of which he had many, and they responded enthusiastically to this tasty fruit from afar. One was Peter Collinson, who had a business relationship with American horticulturalist John Bartram. Bartram had for years been sending Collinson regular shipments of American plants he’d either grown or collected; Collinson in turn sold them to English aristocrats intent on filling their estates with the “exotic” plants of the new world. Within months of trying Franklin’s Newtown Pippins Collinson was asking Bartram to send him grafted trees and/or scion wood, which Bartram did, though he complained that he thought there were better apples. Another was Dr. John Fothergill who seems to have given some apples to explorer Joseph Banks, probably in dried form. Banks took them with him as he explored the South Seas with Captain James Cook and the HMS Endeavour between 1768 and 1771, including Tahiti, Australia, and New Zealand. A diary entry for December 1769 notes that they made an excellent pie.

By the 1770s, newspapers throughout the UK were advertising Newtown Pippin nursery stock for sale, and orchardists across the land were trying to grow their own–and largely failing. Plants have their place, their terrior, and Newtown Pippin wasn’t meant for England’s cooler, damper climate. Even prominent horticulturalist William Forsyth, superintendent of the royal gardens at Kensington and St. James’ Place, admitted that “[t]he New-Town Pippin is a fine apple in good season, but seldom ripens with us,” (A Treatise on the Management and Cultivation of Fruit Trees, 1803).Enterprising merchants set about importing apples instead, slowed down only a little during the few years it took for the colonies to break their political ties with the motherland. The demand did nothing but increase after 1834 when Andrew Stevenson, Minister to the U.K. under Andrew Jackson, and his wife Sally sent the newly crowned Victoria a basket of Newtown Pippins grown in their home state of Virginia (where they went by the name Albermarle Pippin). The apple proved to be such a delight to the royal household that the excise duty applied to the importation of apples was lifted for that variety only.

With a ready and enthusiastic market available, American farmers planted Newtown Pippins by the thousands. On the east coast they became a signature apple in Virginia, New York’s Hudson Valley, and the shores of Lake Ontario, with farmers shipping apples by the ton to English markets. They traveled west as European settlers did, and really took hold in the western states because of their ready access to international shipping channels. Newtowns arrived in Oregon with Henderson Lewelling in 1847 and spread from there, north to Hood River, for example where exports started in the 1890s and where they are still grown today.

Newtown Pippin headed south, too, first to the Gold Country around Sacramento in the early 1850s, then to California’s Pajaro Valley near Watsonville, an hour and half south of San Francisco. Exports from the area started in the 1870s, first to the fast growing city of San Francisco, then farther afield to Great Britain and it’s colonies in Australia and the far east. It also became the signature apple of Martinelli’s cider company, which started in the 1880s making fermented cider but segued into sweet sparkling juice when Prohibition reared its ugly head. Newtown Pippin was, and still is, the mainstay of Martinelli’s cider, so even as exports eventually fell off in the 20th century, though it took many decades, farmers kept those old trees in the ground instead of replanting with fancy new market varieties like Honeycrisp.

The popularity and importance of Newtown Pippin cannot be underestimated. It has not only been grown on a commercial scale continuously in the U.S. for the last 300 years, but in South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia as well. And though today you are more likely to find it as a fresh apple at a farmer’s market or roadside fruit stand, where it will undoubtedly be labeled simply Pippin, there are still a significant number of Newtown Pippin orchards around, meaning Newtown Pippin is one of the most widely available single varietal ciders in the country.

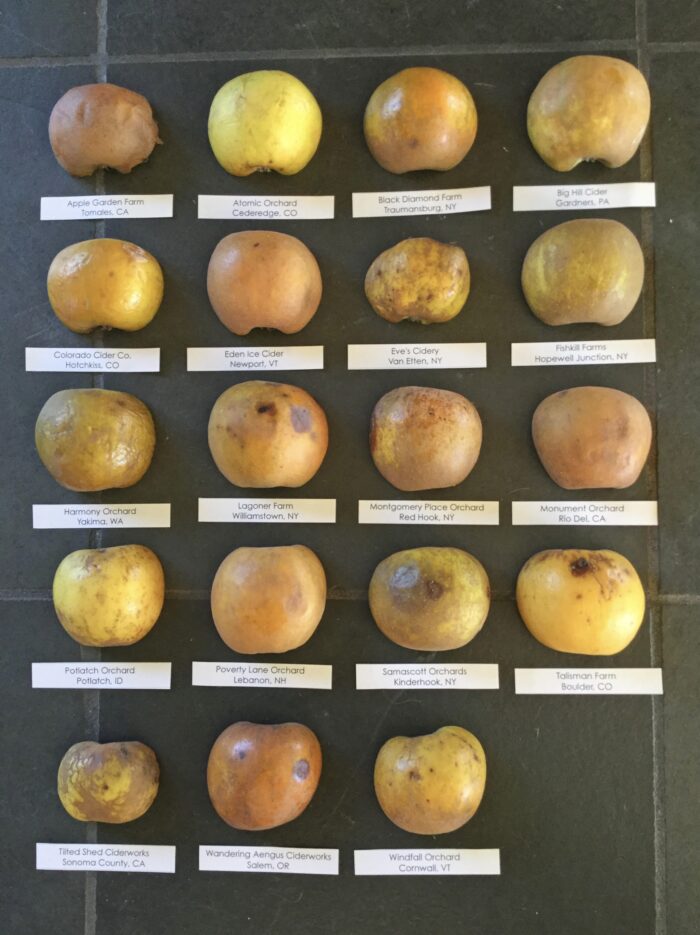

I’ve been evaluating, and collecting, Newtown Pippin ciders for the last five or six years and had more than two dozen to try recently, some of which I’d had before. To be frank, most of the older ones had not held up that well. What had been lively and interesting flavors in 2018, when they’d been in bottle just a year or two, were now faded to almost nothing, not oxidized or flawed, just gone. To age well, wine, and presumably cider, needs a couple of things. The first is structure, significant acid or tannin or both to allow it to evolve into something more interesting with time. The second is a certain intensity of flavor, enough of those wonderful aroma and flavor components to morph from fresh bright fruit to honeyed, dried versions, for example. My memory tells me that these older ciders had the latter, but it seems not the former. Newtown Pippin in general does not have much in the way of tannin, though there are exceptions, and the ciders that had not held up had only moderate acids levels. If a cider I try is not at its best, it doesn’t get included, so that’s all I’ll say about them here.

There were several exceptions made from apples harvested in 2016. Two, made by Angry Orchard and Liberty Ciderworks, still had some of the highest acid levels of any of the older Newtowns I tried giving them that needed structure. The others were two ciders made by Tilted Shed Ciderworks. The fruit for these came from two different orchards, one in the Pajaro Valley near Watsonville and the other in Sonoma County, but both were dry-farmed (no irrigation or meaningful rain from at least April until October). They were pressed and processed separately using the traditional method, en tirage for 16 months before being disgorged. In early 2018 each was distinguishable from the other, the one from Sonoma County full of intense flavors of root beer, lemon, and peppermint and the Pajaro Valley example showing more notes of baking spice and savory dried herbs. What was truly interesting, however, is that both had two to two and a half times as much measurable tannin as any of the 30-some-odd Newtown Pippins sampled at the time, as much as is typically reported for Kingston Black apples (2 – 2.5 g/L). You could feel it in the cider’s body as well. Dry-farmed fruits, whether grapes or tomatoes, have a well-deserved reputation for a greater intensity and complexity of flavor, and in these examples that orcharding practice may well have pumped up the tannin content of the apples, too.

As for the Newtown Pippins of more recent vintage, their acid levels were generally moderate, and though tannins were noticeably present, more so than one might expect from what is generally considered a table apple, the levels did not approach those of the dry-farmed fruit. There was often a savory herbal quality and tropical fruit notes, especially those made from apples grown in a more Mediterranean climate.

Scar of the Sea Wines, San Luis Obispo – dry; lemon juice, lemongrass, melon, dried apple, dried pear, dried thyme; sparkling; 2018; 8% ABV

Haykin Family Cider, Aurora, CO – semi-dry; ripe yellow apple, ripe pear, pear sauce, lemon, honey, ripe peach; sparkling; 2017; 6% ABV (apples grown in Yakima, WA)

South Hill Cider, Ithaca, NY – dry; green apple, green apple skin, green plum, dried apple, slight bitterness; sparkling; 2019; 8.6% ABV

Potter’s Craft Cider, Charlottesville, VA – dry; fresh green apple, mango, allspice, green pear, thyme, toast, bread dough, smoke, slightly bitter; sparkling; 2020; 8.4% ABV

Tanuki Cider, Santa Cruz, CA – dry; tart yellow apple, lime zest, lemon pith, dried herbs; sparkling; 2020; 8.5% ABV

Ethic Ciders, Sebastopol, CA – dry; cardamon, nutmeg, mango, lemon rind, honeysuckle, nectarine, pineapple, rose; sparkling; 2021; 7.5% ABV

Golden State Cider, Sebastopol, CA – dry; hay, dried twigs, ripe yellow apple, lemon rind, dried thyme, melon; sparkling; 2021; 7.9% ABV

Two Broads Cider, San Luis Obispo, CA – dry; fresh yellow apple, pineapple, fresh thyme, fir tips, lemon, apricot, pear skin; petillant; 2019; 8.5%

Angry Orchard, Walden, NY – dry; smoke, jalepeño, dried thyme, dried apple, stewed pear; sparkling; 2016; 8.8% ABV

Liberty Ciderworks, Spokane, WA – dry; ripe yellow apple, fresh and dried, pear skin, lemon juice, dried apricot, dried thyme; sparkling; 2016; 7.2% ABV

Tilted Shed Ciderworks, Windsor, CA – dry; dried green herbs, dried apple, dried pineapple, lemon juice, lemon pith, green plum; sparkling; 2016; 9% ABV (apples grown at Vulture Hill, Sonoma County)

Tilted Shed Ciderworks, Windsor, CA – dry; dried apple, dried pear, dried thyme, lemon peel, lemon pith, dried mango, dried oregano, honey, creamy texture; sparkling; 2016; 9% ABV (apples grown at the Five Mile Orchard, Pajaro Valley)