How does an apple become famous?

In 2021 there would certainly be a PR firm involved and a social media campaign complete with foodie influencers and sexy images. Nothing of the kind existed in the 19th century, so how did far flung farmers and apple consumers get the word on the Next Big Thing? Newspapers were key, of course, for every county seat and most towns with more than 500 inhabitants had at least one or two weeklies, but to establish a reputation for excellence an apple needed a champion. For the Jonathan apple that champion was Jesse Buel (1778-1839).

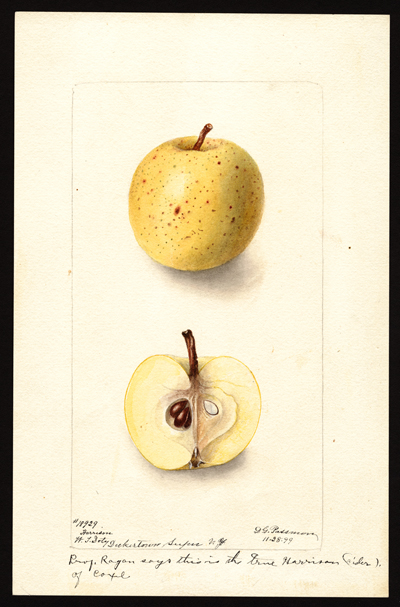

The apple that became Jonathan was an Esopus Spitzenberg seedling planted on the Woodstock, New York farm of Philip Rick(s) (1745-1828), probably sometime around the turn of the 19th century. Ricks undoubtedly shared what he thought was a pretty good apple with family and friends, one of whom was Jonathan Haasbroek, godfather to one of Rick’s sons. Haasbroek, in turn, brought the apple to the attention of Buel in the early 1820s.

Buel was in the perfect position to turn a local favorite into a national phenomenon. A self-made man, he apprenticed to a printer at the age of 14. Though having had just six months of formal education he was apparently a quick study as he mastered his craft in four years instead of the usual seven. Securing release from his apprenticeship, he moved to New York, first to Manhattan, then to various towns in the Hudson Valley, eventually settling in Kingston where he likely became friends with Jonathan Haasbroek, another Kingston resident. He founded his first publication in 1797, the Northern Budget, followed by the Guardian, the Political Barometer, the Ulster Plebian, and the Argus. He was appointed Judge of the Court of Common Pleas for Ulster County, and, after moving to Albany in 1815, was chosen printer for the State of New York.

The success of his publications, the anti-Federalist Plebian in particular, had allowed him to create quite a nice life for himself and his wife Susan, accumulating considerable property both personal and real. It came as a bit of a shock to some then when, in 1821, he divested himself all his publishing interests and announced he was devoting his energies to agriculture and its improvement (including cidermaking). Though having little practical experience of farming, Buel had spent years thinking about it and studying treatises on the latest practices. “There is no business of life which so highly conduces to the prosperity of a nation, and to the happiness of its entire population, as that of cultivating the soil,” he wrote in 1839.

Buel was right in the thick of the 19th century agricultural reform movement. Proponents advocated “scientific agriculture”, and the movement sparked the formation of countless agricultural societies and a robust agriculture-specific press. Northeastern farmers in particular were faced with a number of challenges. Soil fertility was declining, infestations of crop pests and diseases were worsening, and rising competition from midwestern grain farming was forcing a shift to new crops. Buel’s 85 acres in the Sandy Barrens west of Albany became his experimental nexus, and as he learned he wrote–articles, books, and letters to like-minded agriculturalists. He became the recording secretary of the New York State Board of Agriculture in 1822, a state assemblyman in 1823 where he served on the committee for agriculture, and a corresponding member of the Horticultural Society of London in 1825.

The first published mention of the Jonathan was in a printed version of an address given by Buel to the New York Horticultural Society (not to be confused with the Horticultural Society of New York) in 1826. He was pushing for a comprehensive list of all available apple varieties and their various attributes that could help farmers make intelligent planting choices and included an example of such a list with “some of the most valuable Apples propagated in the Nurseries of this State.” Jonathan is number 39, though here it is called Ulster Seedling (new) and described as “less tart than Esopus Spitzenberg, fruit much desired.” He sent fruit to the Horticultural Society of Massachusetts in 1829 (“Jonathan, or New Spitzenbergh…superior to the old for eating”) and scions to the Horticultural Society of London in 1831. By the 1830s, pieces like the following were appearing in agricultural journals throughout the northeast, “From Judge Buel of Albany, the Jonathan Apple, a new and superior fruit, and esteemed in its season, by him and other good judges…as one of the most beautiful, excellent, and admired of all known…Skin thin, of a pale red, blended with faint yellow…Flesh very tender…Juice very abundant, rich, and highly flavored…Named in compliment to my friend Jonathan Harbrauck, Esq.”

People took notice. By the end of the century it was grown in just about every state in the country, and newspaper ads trumpeted the arrival of Jonathan apple season.

So admired was the Jonathan that it became a staple in many 20th century apple breeding programs and a parent of popular apples such as Jonagold, Jonamac, and Idared. And though other modern apples have perhaps eclipsed it in sheer numbers grown, Jonathan apples are still important in the marketplace, appearing in stores around the country every fall like clockwork.

Though historically Jonathan was not considered an apple for cider, the handful of Jonathan varietal ciders that have appeared in the last few years are a testament to what is possible when interesting apples are grown with cidermaking in mind then thoughtfully treated in the cidery. The 2016 Tilted Shed is a case in point. The apples were harvested from large, mature, organic, dry-farmed trees, and in Sonoma County, CA that means essentially no water from about April until late October at the earliest. This stresses the tree, of course, and while reducing over-all productivity the fruit that is produced is typically richer and more concentrated in flavor. The must was treated in the traditional manner of a fine champagne–fermented and aged in neutral, French oak barrels, bottled and kept on tirage for nine months, then riddled and disgorged. When it was released in 2018 its flavor was full of rich, ripe fruits. By early 2021 the cider had matured, taking on flavors of roasted hazelnuts and cardamon, a fine example of how a well-made cider with the right structural components can age gracefully.

All these examples share moderate acids and a variety of ripe fruit flavors, perhaps because all the apples in these ciders were grown in the warmer arid west. It would be most interesting to try a Jonathan cider made from apples grown in a colder, wetter place.

Tilted Shed Ciderworks, Windsor, CA – dry; orange marmalade, mandarin, pineapple, ripe cantaloupe, lemon juice, brioche, pear skin, cardamon, roasted hazelnuts, almond; sparkling; 2016; 9.5% ABV

Blindwood Cider, San Leandro, CA – dry; baked apple, baked pear, orange zest, cinnamon, vanilla, orange juice; sparkling; 2018; 7.9% ABV (dry-farmed apples grown in Sonoma County, CA)

Haykin Family Cider, Aurora, CO – semi-dry; ripe apple, quince, banana, pineapple; sparkling; 2017; 7.4% ABV (apples grown on Colorado’s western slope)

Horse and Plow Winery, Sebastopol, CA – dry; melon, ripe apple, pear, nectarine, mango, orange; sparkling; 2018; 8% ABV

For the consummate apple nerds among you, there is one other story about the Jonathan apple that you should know.

In 1804, a woman named Rachel Negus married a Jonathan Higley, Jr. moving with him from Connecticut to Windsor Township in the newly admitted state of Ohio. The Higleys were one of the first families to settle in the area, which never did develop much. At the end of the 19th century, at the height of the Jonathan’s popularity, one of the Higley’s descendants wrote a book, The Higleys and their ancestry: an old colonial family, that insisted that Rachel Higley was the apple’s true originator.

As the story went, Rachel Higley had gathered seeds from a cider mill as she left Connecticut and planted them near her new home. The result was an apple called Jonathan, and the author was certain that it was this apple that had swept the country. “The original fruit bearing this name is claimed by a horticulturist in Central New York, at much later dates,” the author wrote. “The writer, however, has conversed with a number of aged persons who clearly [my emphasis] recalled the fact that Mrs. Rachel (Negus) Higley gave her first apples, in 1811, her husband’s given name.”

It is perfectly plausible that Rachel Higley grew an apple that she named for her husband and possible that the locals thought highly of it. Windsor Township was, however, at the edge of the Western frontier. There wasn’t much there then, and there isn’t much there now–no newspaper, no railroad, not even much of a town. The Ohio State Pomological Society didn’t exist before 1847. So who would have been this apple’s champion? Who would have introduced it to a wider world and ensured its place in orchards across the country? The Higley Jonathan had no Jesse Buel. Though it might well have been the choice variety the Higley heir believed it to be, it is just one of the many the small-town apples lost to history.