Every new business wants to differentiate itself, to stand out from the crowd. It is a bit of a mystery, then, why so many websites for smaller cider companies proudly state that they are different because they don’t make sweet cider, unlike the big bad Big Players (you know who they are). So many cideries make this claim that it no longer seems to be much of a distinction. More to the point it does an incredible disservice to sweeter ciders, seeming to say that if it’s sweet it’s therefore bad, and implying that if it’s dry it is therefore good. As with most simplistic statements, this ain’t necessarily so.

First, when we talk about sweetness in cider, just what is it we’re talking about.

Sugar is the obvious answer, and how much of it is either left in the cider from the original juice or added back at some point post-fermentation either in the form of un-fermented juice or plain old table sugar. The amount of sugar in a finished cider can be reported in any of a number of ways – in grams of sugar per liter (which can also be expressed as a percentage), specific gravity, or degrees brix (often used in the wine world). There are any number of calculators and tables available that can convert these measurements from one to the other, so for the purposes of this discussion we’ll stick to grams per liter (g/L).

The good folks at the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) have tried to bring some order to the world of cider evaluation by setting some general boundaries for various categories of cider-based on sugar content.

|

Dry |

Medium-Dry* |

Medium |

Medium-Sweet |

Sweet |

|

|

g/L |

0 – 4 |

4 – 9 |

9 – 20 |

20 – 40 |

>40 |

|

% |

0 – 0.4 |

0.4 – 0.9 |

0.9 – 2.0 |

2.0 – 4.0 |

>4.0 |

|

SG |

1.000 – 1.002 |

1.002 – 1.004 |

1.004 – 1.009 |

1.009 – 1.019 |

>1.019 |

(*aka semi-dry or off-dry)

To put this in perspective, regular Coca Cola® has a sugar content of 108 g/L, and freshly pressed apple juice will typically come in at 117 – 260 g/L.

Left to their own devices yeasts will most of the time keep eating up any sugar they find until there is nothing left, resulting in dry cider. But not always. The traditional production method for French ciders, for example, starves the yeasts of other essential nutrients so that they more or less give up before all the sugar has been consumed. The result is a naturally sweet often quite complex and wonderful cider. A similar process can be used in the making of ice cider, which starts with highly concentrated (by freezing and thawing) juice and results in a very sweet dessert cider (upwards of 165 g/L) that more often than not avoids being cloying by wrapping all that sugar around a sturdy backbone of bright acid.

Sugar content isn’t quite the last word on sweetness, though. Our brains can sometimes be fooled into thinking something is sweeter than the actual available sugars would suggest. The amount of acidity in a given cider will, for example, influence how sweet it tastes. A high acid cider that has a sugar content that would put it into the medium cider category may taste less sweet than a low acid cider having a sugar level in the medium-dry range, which is also why to many palates fresh apple juice will taste less sweet than a Coke®. Furthermore, because taste and smell are so closely intertwined a fruity aroma will also encourage us to taste a cider as sweeter than it is, while conversely an earthy aroma will make a cider be perceived as less sweet. (Genetics can play a role in sweetness perception, too.)

So why take issue with sweetness? For one thing, it’s an easy target. The most common complaint of people that don’t like cider is that it is too sweet. Generally this kind of statement suggests that the speaker hasn’t had the opportunity to try many ciders, and certainly the ciders offered by the Big Players are on the sweet end of the spectrum. What’s more, the Big Players muddy the waters by labeling some of their offerings as “dry” when on an objective basis they are anything but.

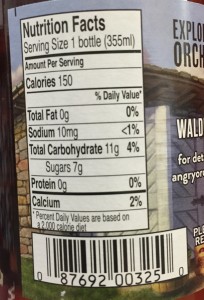

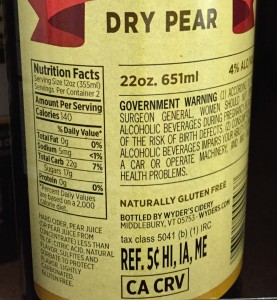

Take a couple of examples produced by some of the nationally distributed large brands. One “dry” cider has, according to the label, 7 grams of sugar in a 355 ml serving, which works out to 19.7 g/L of sugar, on the high side of medium. Another labeled as “dry pear” has a whopping 17 grams of sugar per 355 ml serving, coming in at an astonishing 48 g/L, so far from dry that it can’t even see it in it’s rear view mirror.

Why, one might ask, don’t the Big Players make actual dry ciders if, as one assumes from the marketing pitches of their smaller competitors, there is in fact a market for them? The easy answer is that while there are those that do prefer drier beverages, Americans as a whole seem to prefer their drinks sweet, particularly in an emerging category or market.

More to the point, it’s actually more challenging to make a decent tasting dry cider than a sweet one. With a truly dry cider there is nowhere to hide. It requires more attention to apple varieties and blends, and to production dynamics, in order to create something that isn’t just a complete thin and watery acid bomb. In addition, when you are starting with juice concentrates, which once a company is making cider at a certain scale is an absolute must, it is simply impossible to add back all of the subtle complexities inherent in fresh juice that get stripped out during the concentration process. Sugar can make this diminished character less obvious, although at some point all you can taste is the sugar itself rather than the harmonious flavor you’d get from actual juice.

Dry shouldn’t be the considered the ultimate goal. There are certainly as many uninteresting dry ciders on the market today as there are sweet ones, and more than a few that could be rescued by just a little more attention to balance. Complexity, proportion, nuance – those are the watchwords of a great cider regardless of where it sits on the sweetness scale.

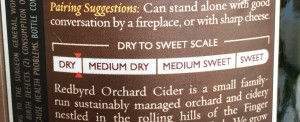

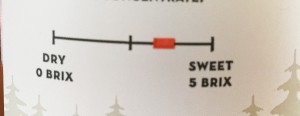

There are a handful of cider companies (such as Seattle Cider Company and Redbyrd Orchard Cider) that have taken it upon themselves to add some sort of scale information on their label in an attempt to help consumers find their way through the fog. This sort of information along with the writings of thoughtful reviewers, those that work hard to describe a full range of a cider’s characteristics not just whether or not they liked it, can help to bring some clarity to an otherwise murky area.

Meanwhile, here’s hoping that the next time a new cider company’s marketing team sits down to describe what sets the company apart he/she/they work a little harder to find something a little more original to say.